Today is ‘International Day of Forests’. It is also the last day of my six month practicum of training with the Association of Nature and Forest Therapy. Very soon I will be a Certified Guide. In the last week I’ve been reflecting on this journey and how this all come about.

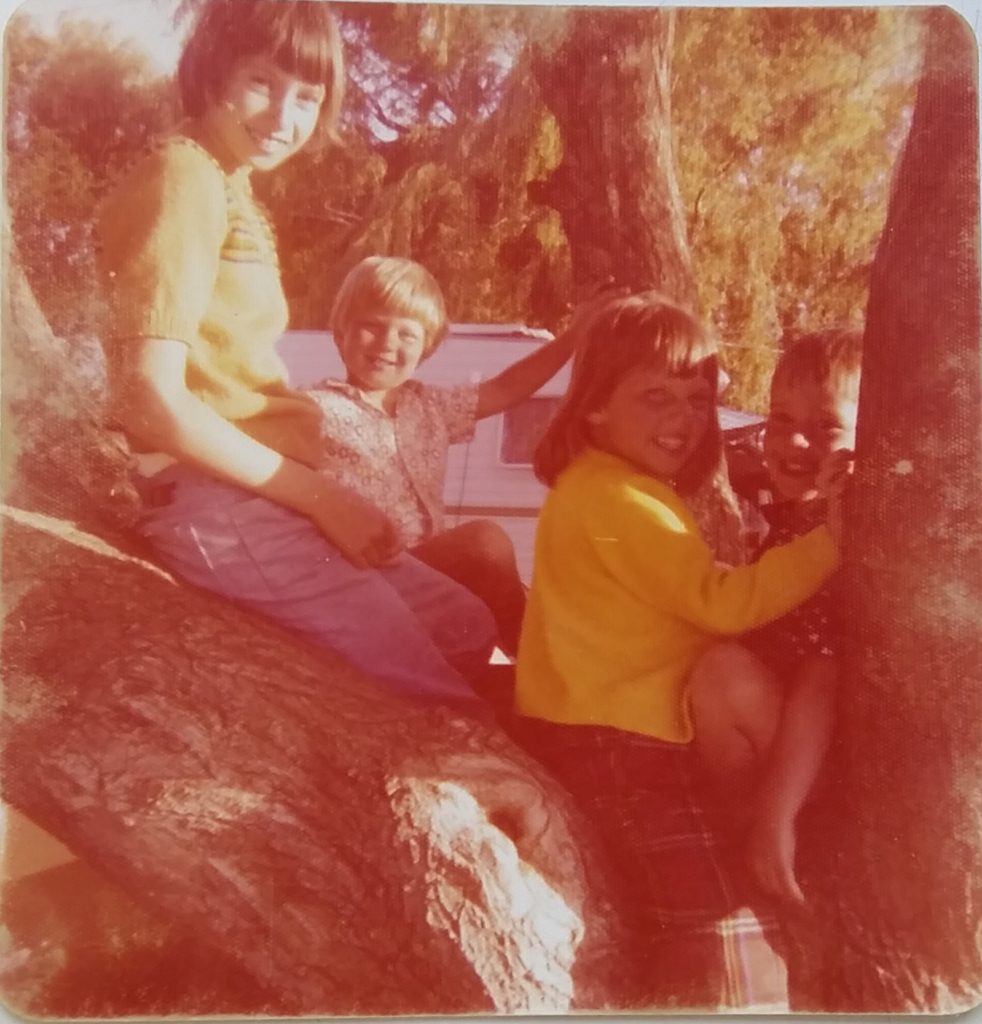

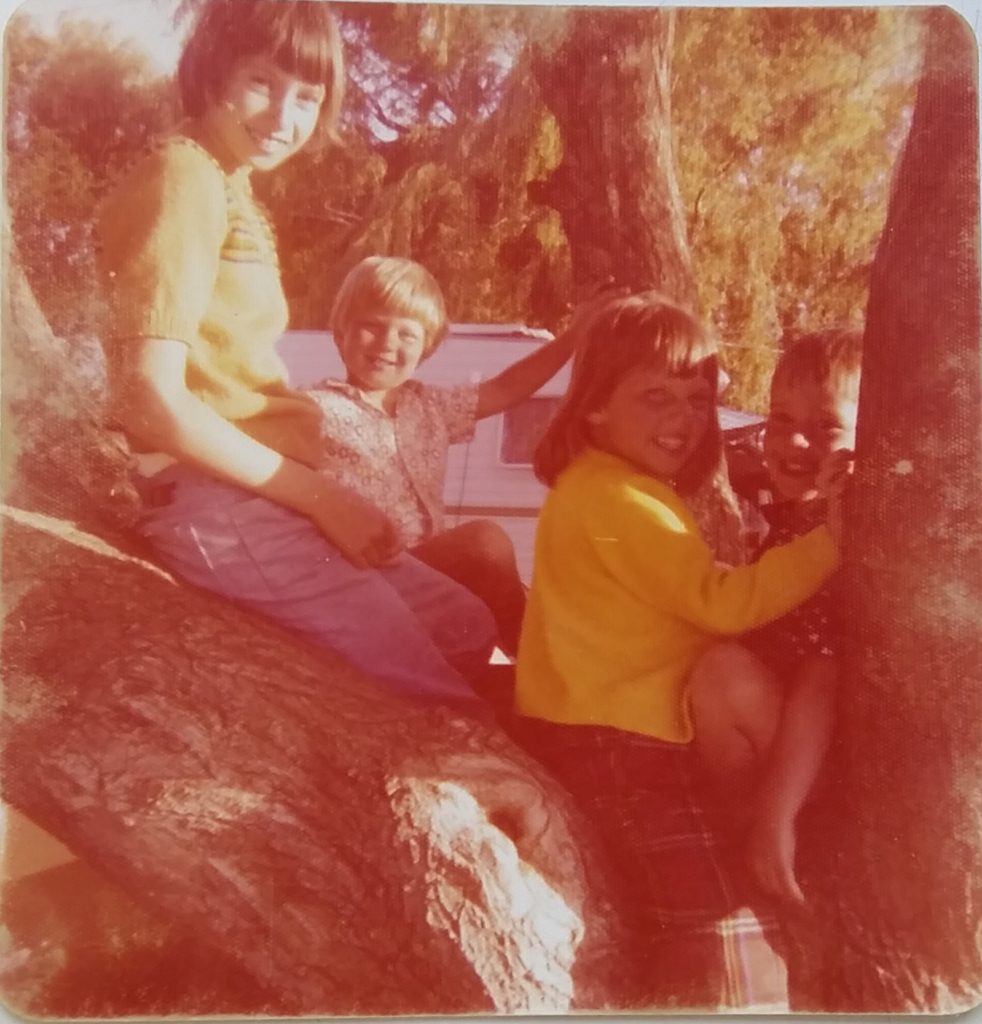

I think it all starts back in my childhood when I spent most hours outside on the farm in country Victoria. I have fond memories of the vege garden, looking after animals, bike riding on country roads and driving the tractor for dad. I didn’t spend much time inside, preferring to generally wander the paddocks amusing myself, kicking field mushrooms or throwing cow pats like discuses. I used to spend hours lying on a big branch in an old gum tree, making up stories in my head about the creatures that lived there. Nature was my playground.

I’ve always loved playing in trees.

As you do, I left home at 21 thinking there was something better. I got married young, had a family, bought my first house, travelled overseas and moved to a big city to get a degree and pursue a career. It was about accumulating lots of stuff. But Brisbane got crowded and I yearned to get back to a quieter life, so went back to Darwin 11 years ago with my beautiful family in tow.

I was drawn into bushwalking, taking up invitations to hike with friends in Kakadu. I heard about permaculture and joined a community garden. I also had the privilege of being out on country with Aboriginal Elders on the Tiwi Islands and an outstation in NE Arnhemland, where I felt, smelt, sensed and heard stories about their human-nature spiritual connection.

Hiking the Jatbula Trail near Katherine in 2017.

I can now appreciate how lucky I was to have been so close to nature as a child, as I find myself coming back around to many of the practices that kept me grounded and healthy.

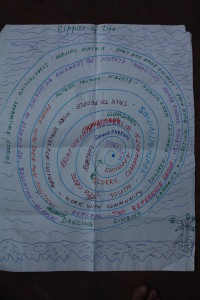

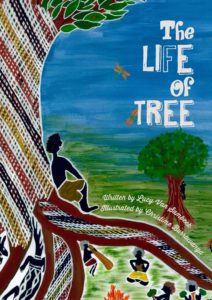

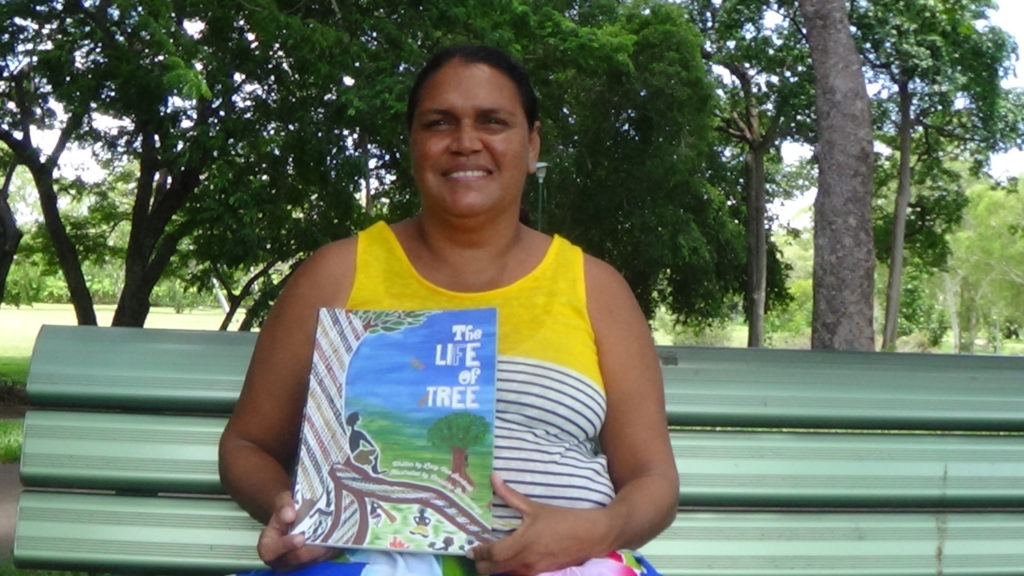

Over the years while practising social work on the Tiwi Islands, I came to learn about narrative therapy and a groupwork methodology called the Tree of Life. After sharing these ideas with some of the Tiwi Elders, I came to realise the power of the tree metaphor in helping Aboriginal people tell their problem stories in ways that were non-shaming and safe, as well as strong stories about healing from the ‘storms’ of their lives, working together like a forest. I discovered that yarning about problems using nature metaphors helps to integrate trauma experiences without retraumatising people. We used these ways of yarning in counselling, groupwork and family healing bush camps. I also write a children’s therapeutic book called ‘The Life of Tree’ to help Aboriginal kids open up about their experience of violence in families.

Trees have become important metaphors in my work too.

In 2013, I caught an early diagnosis of thyroid disease and was told I would eventually have to go on medication. Not accepting this fate, I turned to natural medicine for answers – taking supplements to make up for our mineral-depleted soils, cutting out foods that were contributing to my body’s autoimmune response, quitting my job to de-stress, joining the ‘slow living’ movement, and taking up meditation (although I struggled to make this a daily practice). By 2016 I had no evidence that Hashimotos disease had ever been part of my life. Once again, nature had shown me the way.

In the background, I had a growing sense of unease, helplessness and despair at the state of the planet. I mulled about the future my children would have to deal with and noticed the global trends in increased anxiety, depression and suicide in young people coping with the pressure of modern, domesticated life. I read about ‘nature deficit disorder’ as a result of children’s technology use and the detrimental affect excessive screen time was having on their development. Something has to change and quickly. The earth does not have the luxury of time if we are to repair the damage we’ve done, and at what cost to our own physical and mental health?

Fast forward to April 2017 when I find myself in the wild West of Tasmania. My girlfriend had to pull out of our planned trip at the last minute because of her mum’s terminal illness. I’d never travelled on my own before, and I was constantly thinking about my safety out in the wilderness walking alone. But by the end of my holiday, I had come to enjoy my own company so much, that it took me a while to be around people again. I was also in awe of the beautiful old growth forests that boasted trees that were more than four hundred years old. Nature has always been important to my own growth, health and wellbeing. But this experience took me to a level of nature connection and a sense of freedom, that I’d never experienced before. I wanted more. It was shortly after this that I heard about Nature and Forest Therapy (NFT) and decided to train as a Guide in September 2017.

Learning how to be on my own in nature in Tasmania’s wild West.

I experienced an amazing week-long intensive immersed in the Yarra Ranges engaging in mindful walks in nature every day. NFT is inspired by the Japanese practice of Shinrin Yoku or forest bathing. While learning the skills of helping others slow down using intentional invitations to connect with nature and ignite the senses, I learnt how to slow myself down even more. Believe me, it is intensive. Practising mindfulness every day takes discipline and practice when you are the kind of person that always has multiple projects on the go and a mind that never rests. After a week, I just wanted to run or go for a long hike. No more slow! But seriously. This is the practice that is going to sustain my health and wellbeing long into the future. And there are a lot of scientific studies coming out now to prove it. For me, it’s about finding the balance between living and working in the ‘real world’ and engaging with the ‘natural world’. As Richard Louv says “The more connected to technology we become, the more nature we need to achieve a natural balance.”

Me and my fellow Guides during our training intensive in the Yarra Ranges.

Over the past six months I’ve learnt a lot about myself – about my ‘edges’ and how to dissolve irrational fears; about how to let go of agendas and trust nature will lead the way; what it means to live out your life according to your values and beliefs even when the chips are down; what it feels like to be part of a community of like-minded folk who also care about the planet and each other; the relief of discovering the beauty in humanity; and finding hope again after experiencing the resilience of nature. I have a long way to go but I’m feeling much more connected to the more-than-human world than ever before. On one of my recent Nature and Forest Therapy walks someone said ‘I’ve been practising mindfulness meditation for years, but I’ve never experienced anything like this before.’ I know right? I’ve been there. And now as an NFT Guide, I get to witness the personal profound insights others gain on my three hour slow wanders in nature. I’m also buoyed by the possibility of people being inspired to take action against climate change and in their personal daily habits, because of their renewed sense of connection and care for the planet. NFT has the power to do this too!

Guiding a Nature and Forest Therapy walk in Nambucca State Forest.

As I come to the end of my practicum I feel incredibly grateful for the support of my mentors, friends and family, the resources that allow me to follow my heart and dreams, and the start I had in life back on the farm that sowed the seeds of nature connection.

Happy ‘International Day of Forests’ to you. Do your body, mind and spirit a favour. Get outside, play, explore, skip, make art using nature’s treasures, gaze at water, climb a tree. Don’t think about it too much. Follow your instincts. And when the forest speaks to you….listen.

This conversation is as delightful as it is authentic. So be warned, Alanna’s heartfelt generosity may inspire you to pack up your city life and go bush.

This conversation is as delightful as it is authentic. So be warned, Alanna’s heartfelt generosity may inspire you to pack up your city life and go bush.