Drug and alcohol misuse, neglect and abuse, violence and early death, overcrowding and ill health. It is a story that is all too well told and re-told about remote Aboriginal communities.

But it is just one story.

The methodology known as collective narrative documentation offers an opportunity for communities to voice an alternative story. One of strengths and skills, customs and traditional knowledge, values and beliefs, future hopes and intentions.

During my time on the Tiwi Islands, I had the privilege of hearing rich stories like this and authoring two collective documents. These documents reflect the words of Tiwi people who have been actively resisting the effects of colonisation, and using special skills and knowledge to stay strong in hard times.

In the narrative documentation process, I witnessed for myself the healing power of storytelling on many levels. The first happened as individuals shared their story around the campfire with members of their family as witnesses to their experience. The second was recognising that they were not alone in their experience as stories were gathered and documented into common themes. And the third happened as their exact words were read back to them. In some instances, I witnessed a fourth step when individuals felt the sense of contributing to the lives of others, by sharing their story with others outside of their community who were also going through hard times.

So how does the process of narrative collective documentation actually work? For a full description of the practice, I recommend reading Denborough’s article in Collective Narrative Practice. But I will briefly summarise the process here as it happened for me.

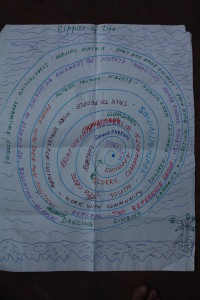

Firstly, you need a gathering of people. For me, the opportunity to collect stories of strength occurred at a women’s healing camp in 2009 and two family bush camps in 2010 and 2011. Next, Denborough recommends a series of questions designed to generate rich content exploring the history of people’s skills and knowledge, and linking this to people and traditions. These are generally as follows:

- What is the name of a special skill, knowledge or value that sustains you through difficult times?

- Tell me a story about this skill, knowledge or value, when this made a difference to you or to others.

- What is the history of this skill, knowledge or value? How did you learn this? Who did you learn it from?

- Is this skill or value linked in some way to collective or cultural traditions?

Sometimes I would ask scaffolding questions, or translate these questions into simpler english, as I was working with people whose primary language was Tiwi. I also gained permission to record people’s stories as an audio file, so that I could go back and translate people’s exact words. When working on your own, I find it challenging to facilitate a conversation and record written notes at the same time. Listening back to audio files obviously takes a lot longer, but I felt it was important to capture people’s exact words in the document, so they would easily recognise them as their own.

Once I transcribed the audio files, I used a highlighter pen to identify common themes amongst the stories. Each theme became a different section of the document. I chose to head up each section with a short phrase I had heard which reflected the essence of that theme.

Writing up the document becomes a narrative process in its self by the author. It is good to begin the document with an acknowledgement in the collective voice of the unique knowledge and skills of the storytellers and hopes for sharing the document with an audience that might resonate with its content.

In the main body of the document, I like to use paragraphs incorporating people’s exact words in quotation marks, beginning and ending with a more general reflection in each section which highlights the collective experience. Other writers cleverly weave together third person and first person talk in each section, in a flowing sequence which captures both collective and individual experience. Every storyteller would recognise some of their own words reflected in each paragraph, even though quotation marks are not used. A good example of this is shown in Denborough’s article. One of my documents incorporates photographs taken on the bush camps that express another aspect of the theme.

The first draft was taken back to the participants to check its content for accuracy. At this stage, there was no agreement to share it outside of their community. After making any necessary changes, copies were made and distributed to the folks that participated. Ideally, permission would be gained to share the documents with other communities or individuals who are also going through difficult times. For different reasons, this never happened and time passed.

Until now.

It is now 10 years since my first collective narrative document was written with the Tiwi people. On my recent visit back to the islands, I finally gained permission from the Tiwi women to share them. It means a lot to them that their hard won skills and wisdom may help someone else, particularly as some of the storytellers have since passed away. It brings them comfort to know that their voice lives on.

It brings me great pleasure to bring share with you the following documents:

After reading these documents I invite you send a response back to the Tiwi community. You may like to use the following questions as a guide to formulate your response.

- As you read this story about, I’m wondering what caught your attention? Which piece resonated with you?

- What image came to your mind as your read this piece? What do you think the storyteller is hoping for, values, believes in, dreams about or is committed to?

- Is there something about your own life that helps you connect with this part of the story? Can you share a story from your own experience that shows why this part of the story meant something to you.

- So what does it mean for you now, having heard this story? How have you been moved? Where has this experience taken you to?

Contact us if you would like your message sent back to the Tiwi community.

Collective narrative documentation is a way of responding to trauma that acknowledges the strengths of communities and has potential to build relationships between communities going through similar difficulties. If you are interested in using this approach with your group or community, please get in touch, to see if we can help.

* Please note: this document may contain the names and images of Aboriginal people now deceased.

References: Denborough, D. 2008, ‘Collective Narrative Practice: Responding to Individuals, Groups and Communities who have experienced trauma’, Dulwich Centre Publications.

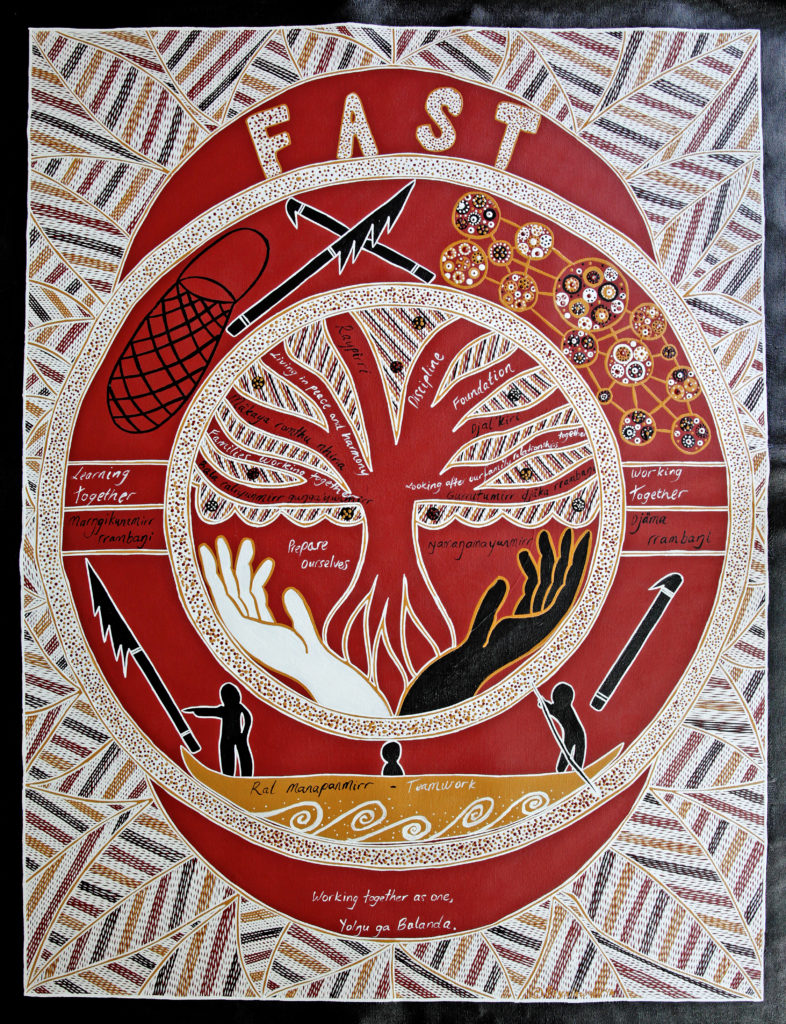

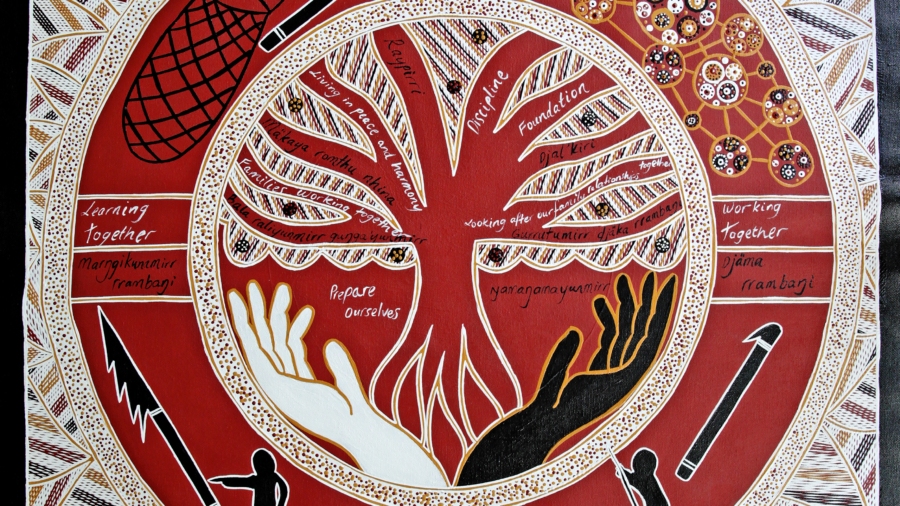

In this episode of Talk the Walk, we delve into the working life of Malcolm Galbraith, Manager of Families and Schools Together (FAST) in the Northern Territory. We discover not only what makes FAST one of the most successful strengths-based programs in remote Australia, but what drives the man behind the project. A man of strong Christian faith, Malcolm admits some of his ideas might be controversial, yet the evidence speaks for itself – Yolngu people love it! Before you scoff at the idea of bringing an American-based program into an Indigenous Australian context, listen to this story. As intriguing as it is thoughtful, this behind the scenes tour of FAST NT may just turn your worldview on its head.

In this episode of Talk the Walk, we delve into the working life of Malcolm Galbraith, Manager of Families and Schools Together (FAST) in the Northern Territory. We discover not only what makes FAST one of the most successful strengths-based programs in remote Australia, but what drives the man behind the project. A man of strong Christian faith, Malcolm admits some of his ideas might be controversial, yet the evidence speaks for itself – Yolngu people love it! Before you scoff at the idea of bringing an American-based program into an Indigenous Australian context, listen to this story. As intriguing as it is thoughtful, this behind the scenes tour of FAST NT may just turn your worldview on its head.