There appears to be a large number of health and allied health professionals who have not even heard of ‘trauma-informed practice’, let alone enact it. To me, it’s a no-brainer. If you work in the Northern Territory, this beats ‘cultural awareness’ training hands-down.

There appears to be a large number of health and allied health professionals who have not even heard of ‘trauma-informed practice’, let alone enact it. To me, it’s a no-brainer. If you work in the Northern Territory, this beats ‘cultural awareness’ training hands-down.

Last week, I went to hear Larrakia man Ash Dargan’s presentation on Trauma-Informed Workplaces, an activity of Reconciliation week for Larrakia Nation. Ash studied under the guidance and mentoring of Professor Judy Atkinson, author of Trauma Trails: Recreating Song Lines: The Transgenerational Effects of Trauma in Indigenous Australia. Perhaps Ash best sums up trauma-informed practice as “looking through a trauma informed lens…where our perspective shifts from ‘something is wrong with this person’ to ‘something has happened to this person’”. It requires a large step away from the Western dominant medical model which has oppressed Aboriginal people for so long. Rather than ‘doing’ to, we can start to think about ‘being with’.

So before we can ‘do’ trauma-informed work, we need a thorough understanding of what trauma is, the complex layers of trauma Aboriginal people have been exposed to since Colonisation and how it plays out in people’s lives today. The ‘babushkas’ diagram which came out of the Healing For Stolen Generations Discussion Paper offers a diagrammatic way to appreciate this complexity that affects individuals, families and communities. Most of us are familiar with the layers of historical trauma – massacres, removal from country, child removal, suppression of culture and language, social control and disease.

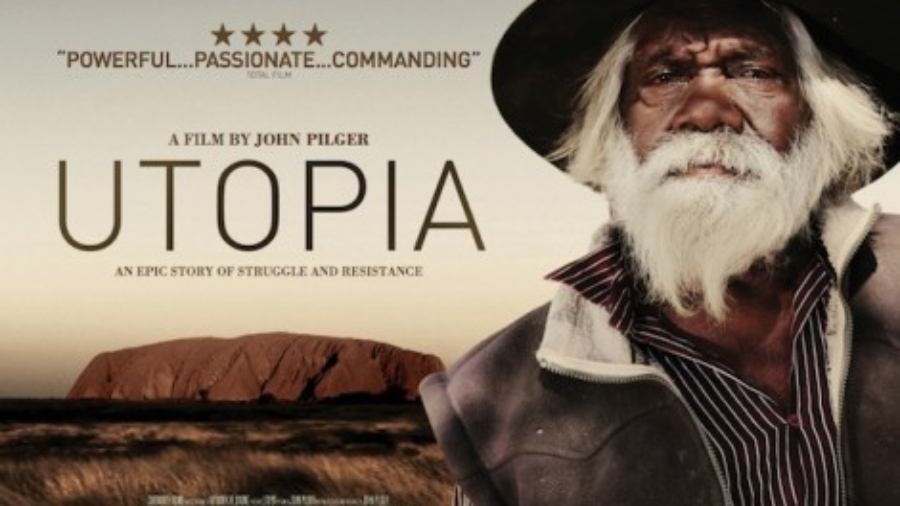

For a different and somewhat controversial perspective, you could watch “Utopia” like I did on Saturday night. I think this was John Pilger’s latest attempt to try to educate the unsympathetic on the impact of the invasion on Australia’s First Nation peoples. It was an attempt to shock the white population using guilt and shame as leverage for social action, however I don’t believe this approach is helpful. Guilt is not my motivation for participating in the Reconciliation Movement nor working with Indigenous people. Social justice and human rights – yes, guilt – no. Ironically, Utopia also appeared to retraumatise some Aboriginal community members from the tone of messages and sadness expressed on Facebook after the show. Anyway, that’s another story.

For a different and somewhat controversial perspective, you could watch “Utopia” like I did on Saturday night. I think this was John Pilger’s latest attempt to try to educate the unsympathetic on the impact of the invasion on Australia’s First Nation peoples. It was an attempt to shock the white population using guilt and shame as leverage for social action, however I don’t believe this approach is helpful. Guilt is not my motivation for participating in the Reconciliation Movement nor working with Indigenous people. Social justice and human rights – yes, guilt – no. Ironically, Utopia also appeared to retraumatise some Aboriginal community members from the tone of messages and sadness expressed on Facebook after the show. Anyway, that’s another story.

Alternatively, Ash offers another way of appreciating the snow-balling effect of First Contact in the ‘generational mapping of trauma’. In the first generation, males were killed and imprisoned and females were sexually abused. The next generation of men turned to alcohol and drugs (freely given by white people) as their cultural and spiritual identity was stripped away and their self worth eroded. The third generation saw men turned on their spouses and society. In the fourth generation, spousal assault turned into child abuse. And in the fifth generation, the cycle starts all over again. Trauma plays out today in unbelievably high rates of imprisonment, substance abuse, racism, child removal, poverty, family violence, lateral violence, and higher rates of suicide, poor health outcomes and lower life expectancy compared to non-Aboriginal Australians.

Ash views First Contact between black and white Australians like a raging bushfire that blazed through the country, out of control, blackening everything in its path. But the smoke is still hanging around. I think that as long as there is no justice or recognition or learning from past mistakes, Aboriginal people won’t be able to see through the smoke. And whitefellas will continue to retraumatise, like the unacceptably high rates of child removal that are still occurring as reported by the ABC on May 26th.

So how does an understanding of historical and contemporary trauma help us ‘do’ trauma informed work? Ash asks us to view Aboriginal people like an onion. We have no idea of the many layers of trauma that they may have experienced throughout their lifetime, and maybe we will only ever peel off one or two. But with an understanding there is more, we are more likely to peel gently and respectfully.

I can’t help but be bought back to the notion of ‘Dadirri’, the inner deep listening and quiet still awareness that Miriam Rose Ungenmerr-Bauman says is in each one of us. She also said “Our people are used to the struggle and the long waiting. We still wait for the white people to understand us better. We ourselves have spent many years learning about the white man’s ways; we have learnt to speak the white man’s language; we have listened to what he had to say. This learning and listening should go both ways. We would like people to take time and listen to us.” The skill of Dadirri has taught me how to sit quiet and listen to Aboriginal people as they tell me their story of abuse or pain or hurt or trauma. But Dadirri invites us to look inside our own hearts. I was reminded of this, in break-time during Ash’s presentation when I bumped into an Aboriginal healer I hadn’t seen for a while. I had hardly said a word, when it felt like he was staring into my heart to see what was troubling me. He simply said the answer is inside me, and to find it I block out all the noise in the room and listen for the silence. Even over the top of loud chatter, I could hear white noise. It was calm and peaceful.

This is what healing is all about. Healing from trauma is not something one can ‘do’ to another. Others can show us the way, but it is something we need to do for ourselves. We have to listen to what is inside our heart. Perhaps trauma-informed work then, is not so much about ‘doing’, but ‘being’.

“We know we cannot live in the past, but the past lives in us” – Charles Perkins

If you’d like to read more on trauma-informed practice, check out my Resource section.