As you may have noticed from previous ramblings, COVID brought a halt to any plans I had last year to travel back to the Northern Territory. As a result, I ended up co-facilitating this Tree of Life workshop on-line with the women of Borroloola.

When 2021 ticked over and COVID restrictions lifted, there were hopes within the Telling Story project to travel to Borroloola in June to share some of the seeds in real life that had been planted virtually. Our aim was to bring back the stories that had been shared by the women and published in their Tree of Life booklet, to gather some more wisdom from others about their skills and knowledge of growing up strong and healthy kids.

My journey took me from Bowraville on Gumbaynggirr country in NSW to Centre Island on Yanyawa country in the Gulf of Carpentaria, a good two days of travel time via jet plane, ute, charter plane, community bus then boat. On the way we collected about 18 women living in the community of Borroloola or nearby outstations; an intergenerational mix of grandmothers, mothers, Aunties and young women from high school. Supported by the hardworking team at the li-anthawirriyarra Sea Ranger Unit and the enthusiastic staff of Indi Kindi, all the logistics of camping gear, food and travel arrangements were sorted. For some of the women, this was the first time they had travelled to Centre Island. It was a healing time to connect with stories of place they had been told from family members or passed down from ancestors.

Our plan was to weave the Tree of Life workshops over the three night camp, allowing spaces for the women to connect with country and each other, yarning around the campfire, fishing, enjoying great food and relaxing. Our first night around the campfire at Black Rock on the McArthur River was an opportunity to introduce the Tree of Life booklet and introduce the process of the workshop with the women. In our first scattering of the seeds, we invited the Indi Kindi staff who contributed stories to the Tree of Life booklet, to share some of their words with the others.

On day 2, we proceeded to make our way out to Centre Island, past crocodiles sunning themselves on the banks of the river, to where endless blue skies kissed the horizon of vast ocean. Much to our unexpected delight we discovered there was generator power connected to the remote outstation shack, a large equipped kitchen, welcoming indoor meeting space, shady front and back verandahs and even a bedroom with aircon. Outside, a large sprawling fig tree set the scene.

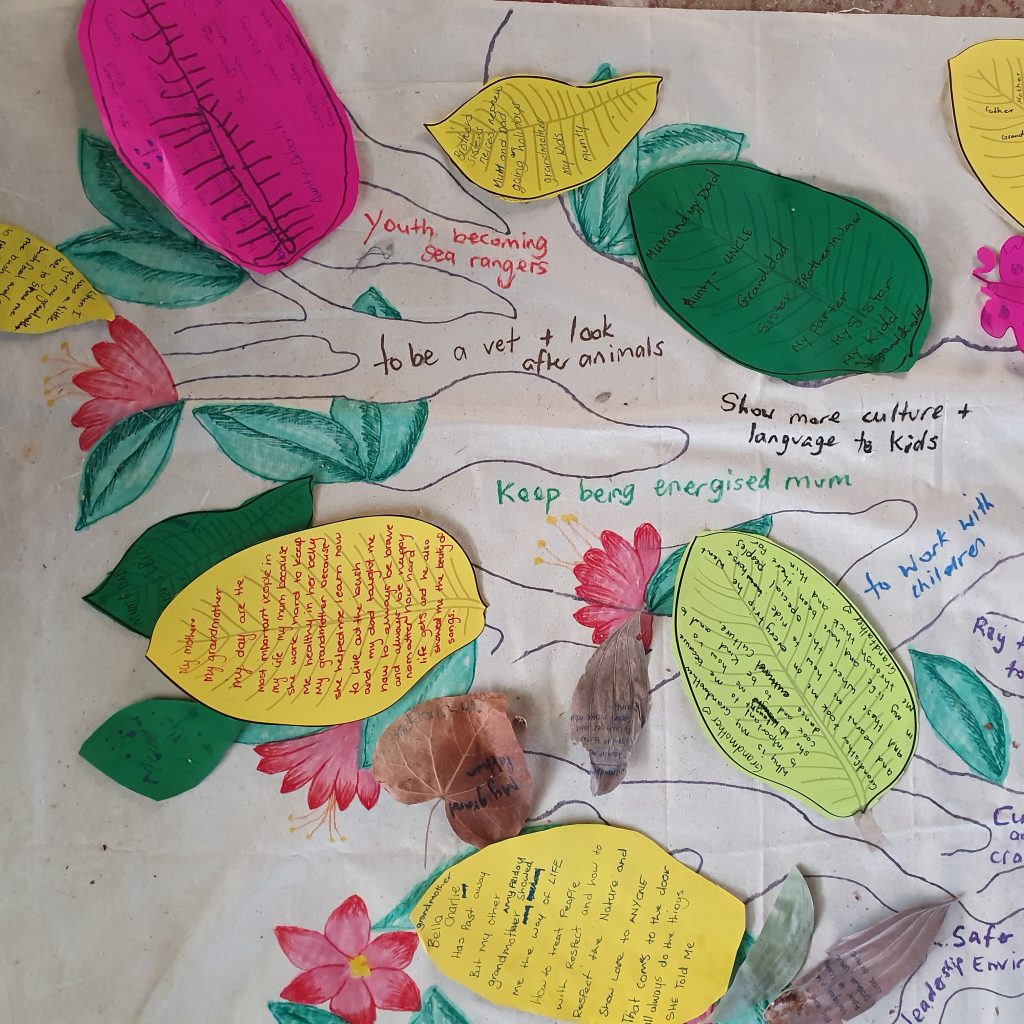

After setting up tents and having lunch, the women were keen to wet a line. I took the opportunity to go exploring and gather materials from nature that might be useful to help people express and record their stories throughout the workshop – things like driftwood to represent roots and leaves to represent the people who are important to us in life. After discovering one of the young women loved art and drawing, we invited her to outline a large tree image on a piece of calico which would become the centrepiece for yarning up strong stories in our circle.

Our afternoon session with the women, began with laying out a set of cards featuring various images of trees and inviting people to share how they were feeling by selecting a card to tell a story. We then introduced the roots of the Tree of Life and invited people to write on a piece of driftwood some words that capture important parts of their family history. Participants spoke their root stories to the group and place their driftwood down on the calico, to start to assemble what would become a collective tree of wisdom. We followed this with a yarning circle about the kinds of skills and abilities women have for growing up strong children and families. Some of the questions that can guide such conversations are:

- What are some of the skills your family has in helping each other? In getting things done at home? In keeping the family together and happy?

- What things is mum/dad/kids/grandparents good at doing for the family to keep strong?

- What is each persons role? How do people in the family come to have these roles?

We can then go on to thicken these stories and make them richer by enquiring about the history of these skills, where they come from and who taught them these skills. We also used Strengths Cards as prompts to help people expand their thinking around their own strengths. As facilitators, we observed that the younger people in our group held back from sharing stories in front of their Elders. There can be cultural reasons why younger people feel shy about speaking up, out of respect. We made a decision to meet with the youth separately early the following day, so that the unique skills of young people are given a voice. During this session, we noticed that the young people would also identify strengths in their friends, naming what they admired about them and why. We also saw these strengths in action, observing later in the day one of the young women teaching another how to throw in a castnet. Such a delight to see.

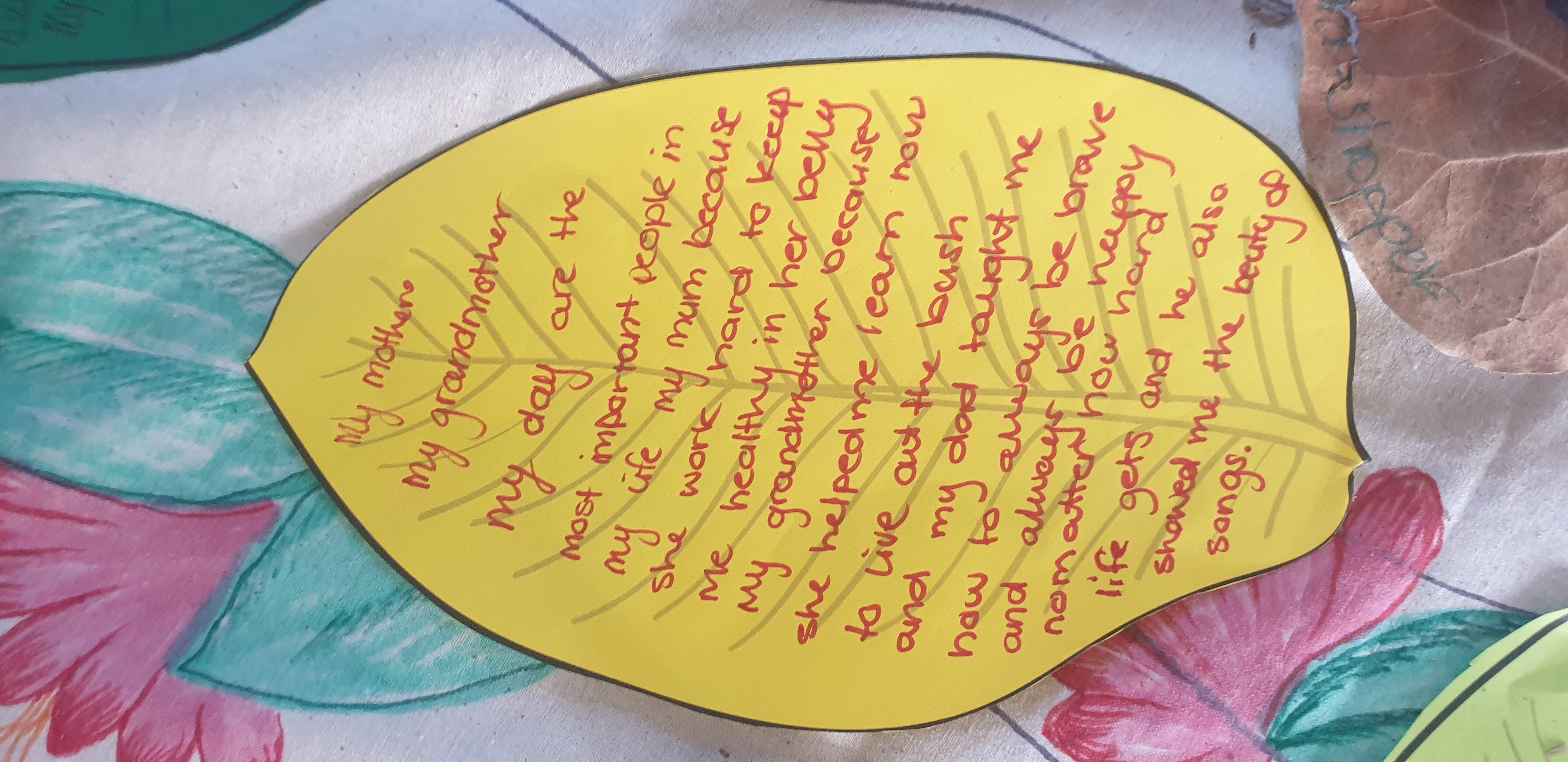

In the afternoon with the older women, we proceeded with yarning up stories about the special people in our lives that help us grow our family strong. Our participants shared stories with a partner then recorded this on a leaf to add to the tree. They also spoke of the fruits or the special gifts that these people had given to them.

Having richly explored the strengths, skills and knowledge of people’s lives, we had created a solid place for people to stand (or what narrative therapists refer to as ‘the safe riverbank position’) in which explore the concept of storms. One of the women shared a story about a special tree on their country. This provided the perfect metaphor for exploring the storms of life.

“On my country was a huge Tamarind Tree. Lots of visitors from Borroloola came out there. It survived so many cyclones. I wonder how old it was? A lot of people were held together under that tree. That tree kept family together, out of the hot sun, sharing stories. Everyone would talk. Cyclone Trevor came through. It didn’t want to go down, that tree. It wanted to grow back up. It has lots of shoots. It wants to stay alive and say “I’m still here”. It’s heard lots of stories that tree. People are working together to keep the tree going.”

The storms of life make us feel not so solid in our trunk. The group named these things as storms in their families and community – violence, deaths in the community, break ins, fighting, being disrespectful towards Elders, drugs and alcohol, suicide, Welfare coming in and bullying. We explored how storms can start with one person and ripple out to affect a whole community.

Surviving storms is harder when you are standing on your own. The group shared ways that they work together and support each other like a forest does, to helps them weather the storms until they blow over.

In our evening session after dinner, we concluded our workshop with sharing stories of our hopes and dreams for the future on the branches of our tree. They included visions they had for themselves as well as their community. Each of the women wrote the actions they might need to take to fertilise these hopes on seed shapes which were added to the ground of the community tree. It is hoped that by naming these intentions in front of other family members, these ideas are fertilised and supported to grow. Participants were also invited to have a photo taken of their hopes and dreams which was framed and sent back to them as a reminder of their commitment.

From time to time, over the few days as our collective tree was growing, we would notice people wandering over to read or reflect on what had been recorded. This also provided an opportunity for the younger women to make further additions away from the group sittings.

Documentation of the rich description of people’s stories is a key part of narrative therapy. At times, this was participants themselves writing some words on elements of the tree. At other times Sudha or I would write on the calico, the essence of what was being shared, in order to capture the wisdom of the whole. One of us would also be writing on notepaper what was being shared. All these actions of story-capturing became part of the final collective document given back to participants.

As the sun rose on our final day, it was time to think about packing up and heading home, back across the waters and to our children, families and communities. Even just a few days away in the quiet and peace of Yanyawa country was enough for people to feel rejuvenated but also homesick for their loved ones.

Opportunities like this wouldn’t be possible without the support of Artback NT, the Moriarty Foundation and the li-anthawirriyarra Sea Ranger Unit. It’s been a privilege to be part of the Telling Story project, an initiative of Founder and Facilitator Sudha Coutinho. Telling Story invites individuals and communities to widen their lens and re-author their stories to find strength, resilience and hope. Visit their page on vimeo to see more of their work.

Invitation to be an Outsider Witness to the women’s stories from Borroloola

Reading the ‘Sharing the Seeds’ booklet about raising strong and healthy kids in Borroloola may spark thoughts about your own skills and knowledge, your hopes and dreams for your children, and help you stand against any storms you may face. If you would like to share these thoughts with the women, you can email Telling Story at sudhacoutinho@gmail.com

Our workshop began with a discussion about what trees mean to the women. We heard stories about the mango trees that were planted by the old people and that sitting under the mango trees brings feelings of connection to ancestors, which keeps women strong. This connection is felt as a voice when the wind blows and the leaves start moving. “We can sense the presence, their spirit is following us wherever we go. We sense the presence of our mothers and fathers, there with us.” The mangoes are like gifts from the old people that continue to feed the children and the future generations.

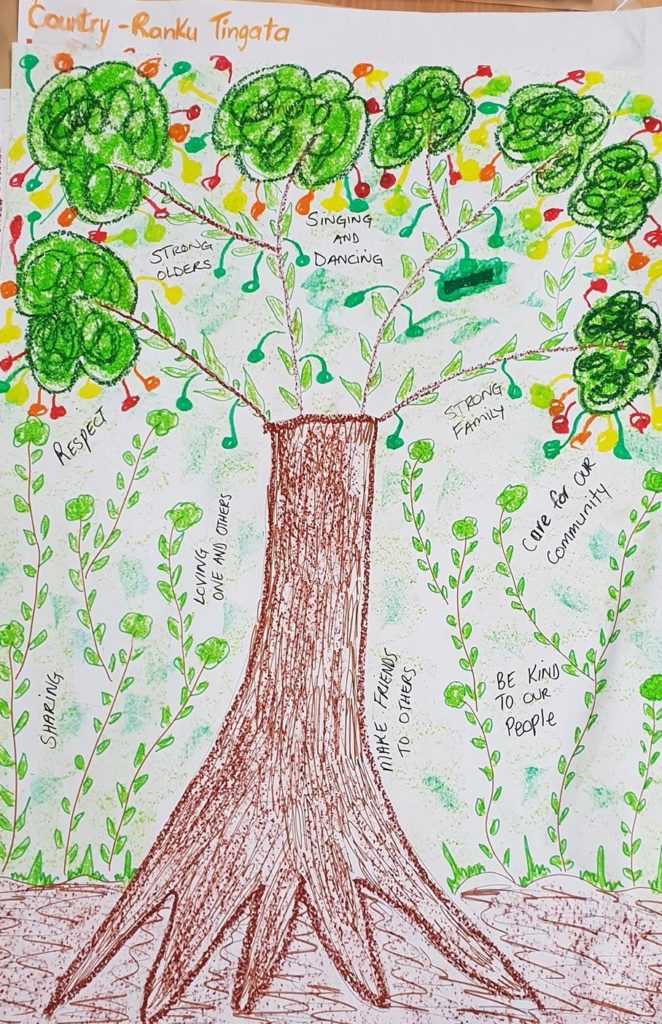

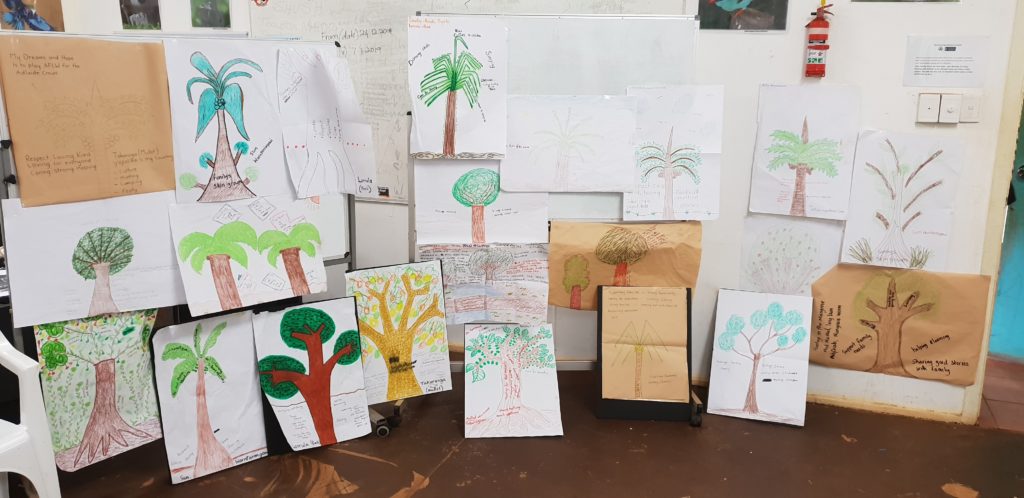

Our workshop began with a discussion about what trees mean to the women. We heard stories about the mango trees that were planted by the old people and that sitting under the mango trees brings feelings of connection to ancestors, which keeps women strong. This connection is felt as a voice when the wind blows and the leaves start moving. “We can sense the presence, their spirit is following us wherever we go. We sense the presence of our mothers and fathers, there with us.” The mangoes are like gifts from the old people that continue to feed the children and the future generations. The next step of the process is inviting the participants to draw a tree, perhaps one that has meaning for them. We provided a variety of art materials such as textas, oil pastels and pencils, giving participants approximately 30 minutes to draw on an A2 size piece of good quality paper. The drawing should include roots, a truck, branches, leaves and fruit (or nuts). We then discuss the role and significance of each part of the tree and introduce the Tree of Life metaphor.

The next step of the process is inviting the participants to draw a tree, perhaps one that has meaning for them. We provided a variety of art materials such as textas, oil pastels and pencils, giving participants approximately 30 minutes to draw on an A2 size piece of good quality paper. The drawing should include roots, a truck, branches, leaves and fruit (or nuts). We then discuss the role and significance of each part of the tree and introduce the Tree of Life metaphor. “I want to be a singer. Nana has been teaching me singing since I was about 15 years old. I want to teach kids how to sing when they grow up. They will teach their kids in the future.”

“I want to be a singer. Nana has been teaching me singing since I was about 15 years old. I want to teach kids how to sing when they grow up. They will teach their kids in the future.” In Day two of our workshop, we explored what it is like to be part of a Forest of Life. The women voiced “We are all one family – we are all Tiwi” as well as recognised the unique stories and skingroups, values and beliefs, skills and abilities, hopes and dreams of each tree. Standing back to visualise the forest of trees revealed the beauty that came from standing tall and proud, healthy and strong. This was seen as a place where the women support each other, look out for each other, offer care, kindness, and protection.

In Day two of our workshop, we explored what it is like to be part of a Forest of Life. The women voiced “We are all one family – we are all Tiwi” as well as recognised the unique stories and skingroups, values and beliefs, skills and abilities, hopes and dreams of each tree. Standing back to visualise the forest of trees revealed the beauty that came from standing tall and proud, healthy and strong. This was seen as a place where the women support each other, look out for each other, offer care, kindness, and protection.

This week on ‘Talk the Walk’ I sit down with Bernard Kelly-Edwards in the middle of his tiny art shop in the thriving alternative community of Bellingen. Bernard is surrounded by paintings, expressions of who he is, a local Gumbayngirr man, and symbols of the deep spiritual connection to country that he shares with others.

This week on ‘Talk the Walk’ I sit down with Bernard Kelly-Edwards in the middle of his tiny art shop in the thriving alternative community of Bellingen. Bernard is surrounded by paintings, expressions of who he is, a local Gumbayngirr man, and symbols of the deep spiritual connection to country that he shares with others.

There’s something about the blue sky, the sparse landscape and the weaving of cultural stories that drew Louise O’Connor to Australia’s red centre. Far from her homeland of Ireland and not satisfied with the big city lights of Melbourne, Louise O’Connor packed up her meagre belongings and head to Alice Springs. She found herself working with the Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantatjara Yankunytjatjara Women’s Council as a Domestic and Family Violence Case Worker and hasn’t looked back. Since arriving, Louise has been drawn to narrative therapy as an approach for working respectfully with Aboriginal women. She now supports a team of case workers implementing the Council’s new domestic and family violence prevention framework developed in consultation with the Australian Childhood Foundation and the large group of women they support in the NPY lands. Louise brought with her a long history of case work with refugees and asylum seekers, youth and people at risk of homelessness or in crisis, both in Australia and Ireland. Louise’s passion for sharing stories and helping others tell theirs shines through in my conversation this week on ‘Talk the Walk’.

There’s something about the blue sky, the sparse landscape and the weaving of cultural stories that drew Louise O’Connor to Australia’s red centre. Far from her homeland of Ireland and not satisfied with the big city lights of Melbourne, Louise O’Connor packed up her meagre belongings and head to Alice Springs. She found herself working with the Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantatjara Yankunytjatjara Women’s Council as a Domestic and Family Violence Case Worker and hasn’t looked back. Since arriving, Louise has been drawn to narrative therapy as an approach for working respectfully with Aboriginal women. She now supports a team of case workers implementing the Council’s new domestic and family violence prevention framework developed in consultation with the Australian Childhood Foundation and the large group of women they support in the NPY lands. Louise brought with her a long history of case work with refugees and asylum seekers, youth and people at risk of homelessness or in crisis, both in Australia and Ireland. Louise’s passion for sharing stories and helping others tell theirs shines through in my conversation this week on ‘Talk the Walk’.

What a delight it was to be speaking with Tileah Drahm-Butler this week on ‘Talk the Walk’, about her journey into narrative therapy and her approach to working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Tileah’s passion for social work and giving Aboriginal people a voice shines through in this conversation. We also gain insight into the woman behind the work and the long list of inspiring women in her family that stand behind her.

What a delight it was to be speaking with Tileah Drahm-Butler this week on ‘Talk the Walk’, about her journey into narrative therapy and her approach to working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Tileah’s passion for social work and giving Aboriginal people a voice shines through in this conversation. We also gain insight into the woman behind the work and the long list of inspiring women in her family that stand behind her.

You don’t have to search too far to listen to the stories of despair, destruction or trauma in Aboriginal communities. These are widely played out in our media. However if we listen with intention much deeper, we will find something richer and more telling. The absent but implicit in these stories, are signs of strength, hope and resilience.

You don’t have to search too far to listen to the stories of despair, destruction or trauma in Aboriginal communities. These are widely played out in our media. However if we listen with intention much deeper, we will find something richer and more telling. The absent but implicit in these stories, are signs of strength, hope and resilience.