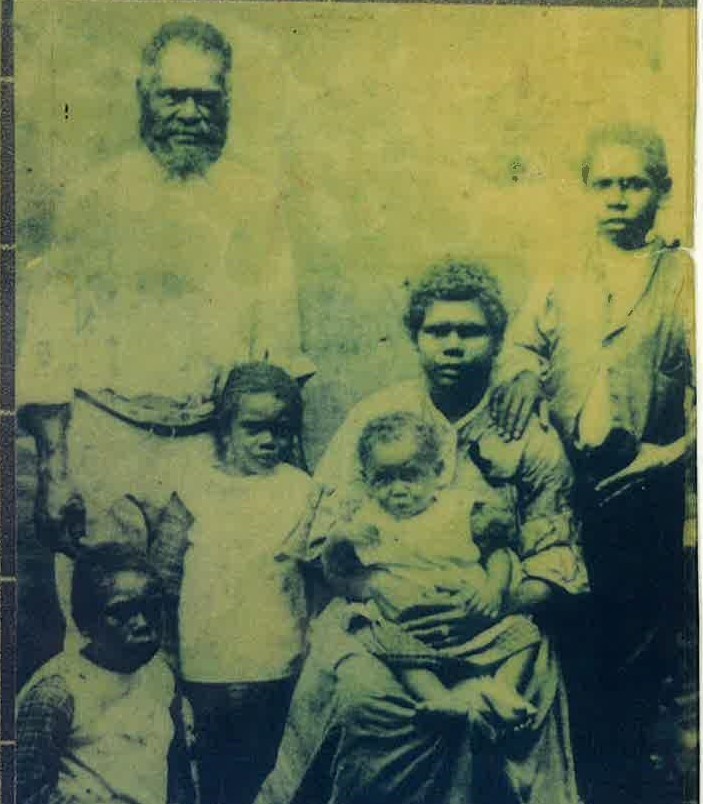

Alison with a local Centrelink worker on the Tiwi Islands

On Episode 6 of ‘Talk the Walk’ I sit down and chat with Alison Grant. This is the first time we had met and it seemed appropriate to invite her along to my favourite haunt in Darwin, a community café run by volunteers at my local community garden. This set the scene for a delightful conversation with Alison, full of birds, children playing piano and lots of other people making fun connections over fair trade tea and coffee.

Alison arrived in the Northern Territory in 2010, taking up a locum position at the VicDaly Shire Council to set up a community development and education initiative to reduce the disadvantage of Aboriginal women on surrounding remote communities.

Alison then moved to Wurli-Wurlinjang Health Services in Katherine as the Coordinator of Targeted Family Support Services, a pilot program aimed at reducing the incidence of statutory interventions. Alison worked with families with high needs requiring intensive family supports, due to substance abuse, incarceration, disability, family violence and poverty.

And her current role is just as demanding, flying in and out of remote communities across the NT undertaking crisis intervention, assessments for crisis payments and supporting vulnerable Centrelink customers who may be experiencing financial exploitation, homelessness or domestic violence. Alison also works in the School Enrolment and Attendance Measure program.

Another day in the life of a remote social worker

In this episode of ‘Talk the Walk’ we explore:

- Alison’s interest in language and how she came to be working with Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory

- Humble beginnings noticing cultural differences to her own Fijian heritage

- A typical day in the life of a social worker in a remote community health clinic

- Leaving off the rose coloured glasses and adopting a realistic view of making a difference

- What it’s like being a migrant social worker and living with culture shock

- Providing essential Centrelink services in a remote context

- Why giving back to the community is a driving passion for Alison

- Alison’s biggest struggles as a feminist in a patriarchal world

- The ethics, values and principles guiding Alison in her work

- Insights into the factors contributing to ‘the gap’ in health in Aboriginal communities

- Alison’s top 3 skills, abilities and knowledge for surviving and thriving in remote social work

- Alison’s keys to building respectful relationships

- Differences between social work with Aboriginal communities and other contexts

- Implications of understanding the kinship system

- Alison’s final tip for those starting out their career in this field

So make yourself a cuppa, put your feet up and just click on the Play button below. Join Alison and I as we ‘Talk the Walk’ in our local community.

We hope to have ‘Talk the Walk’ listed on popular podcatchers like iTunes very soon. Or subscribe by email via our Home Page.

Don’t forget, if you or someone you know would make a great interview on ‘Talk the Walk’, send us an email from the Contact Page.

Things to follow up after this episode

Connect with Alison Grant on LinkedIn

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS