A new year is a good opportunity to reflect on the time that has come to pass, as well as set intentions for the future. But there is something to be said about just appreciating the present moment too.

A new year is a good opportunity to reflect on the time that has come to pass, as well as set intentions for the future. But there is something to be said about just appreciating the present moment too.

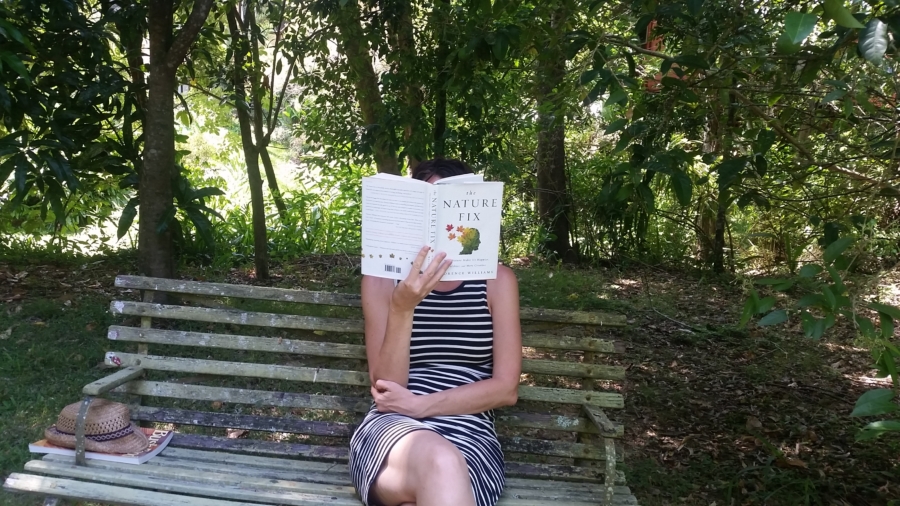

I find myself in a new garden of Eden, set in the Nambucca Valley on the upper mid north coast of New South Wales. The sound of laughing kookaburras echo and the scent of a flowering lemon myrtle wafts over the gentle trickle of Nambucca Creek, winding its way through my backyard. Sweaty tropical wet season days have been replaced with warm, summer days and gentle cooling breezes. I feel my body slowly relaxing into this fresh environment, as culture shock gently subsides and the known but unfamiliar becomes engrained in daily life.

Yes, I have physically relocated. And things are moving for ….metaphorically speaking.

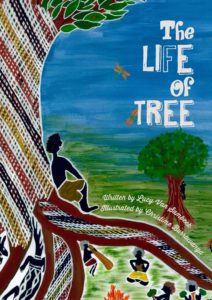

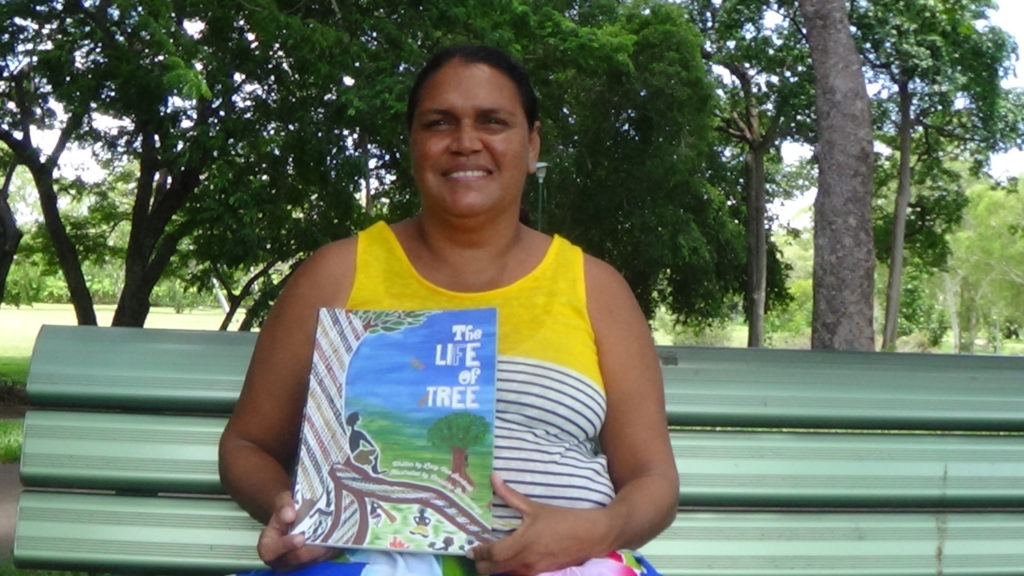

To reflect on the years that have come to pass, I’m reminded of the immense privilege of working in the Northern Territory, the relationships I’ve built that will stand the test of time, a mind-full re-connection to the earth and respect for the oldest culture in the world. My suitcase is full of rich stories, heart-filled memories, learnings and gratitude. 2017 was the year of completion and a sense of accomplishment; seeing out the initial trial of the Healing Our Children project on the Tiwi Islands, Palmerston and Katherine; launching my ‘Talk the Walk’ podcast; and of course, self-publishing my first children’s therapeutic picture book was a thrilling highlight.

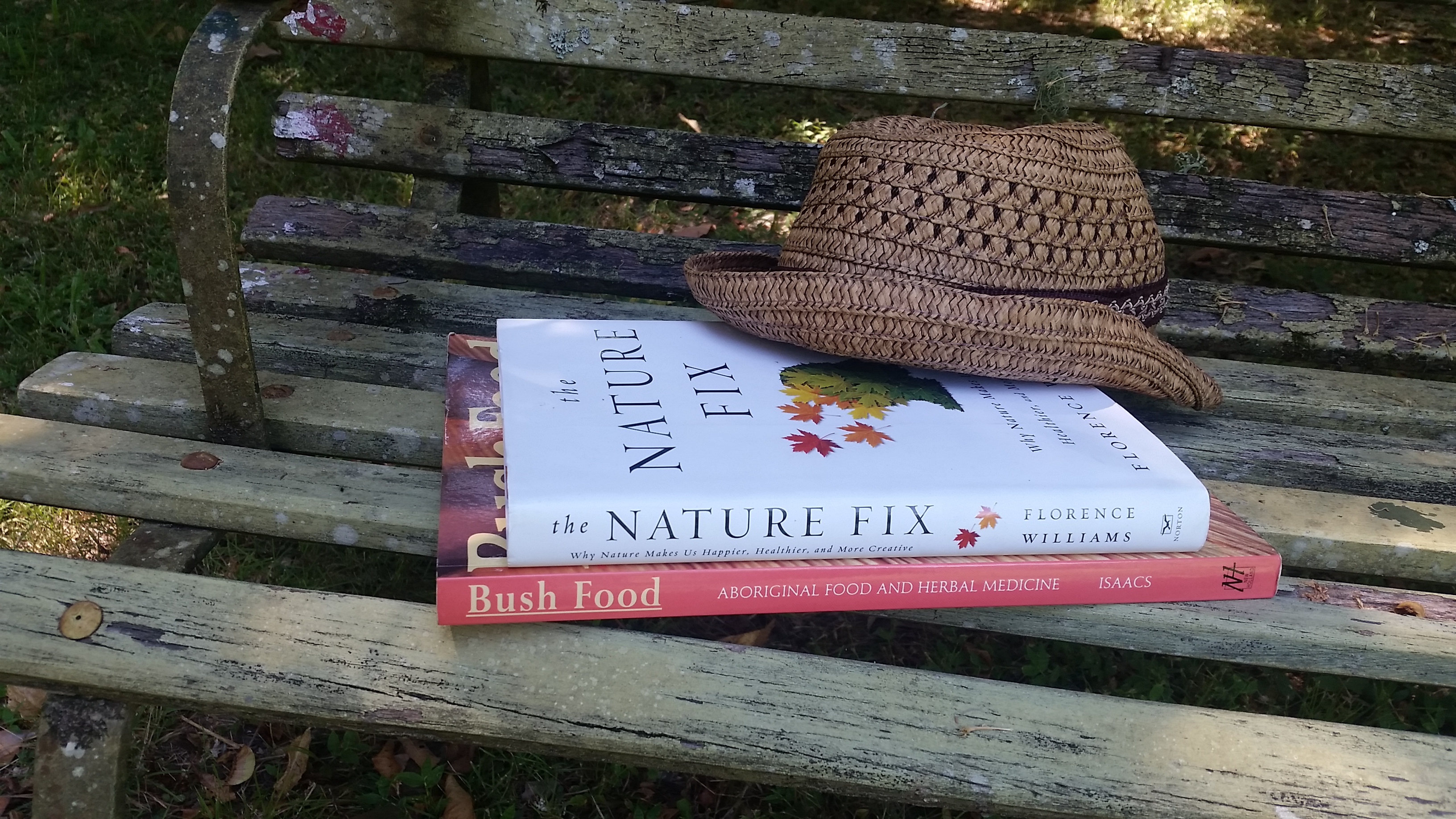

As for new intentions (as I don’t do resolutions) well, there is some exciting opportunities on the horizon. In March I will graduate with a Certificate in Nature and Forest Therapy. I am not sure how the practice of forest bathing will look in the Nambucca Valley yet, but I am buoyed by the hope of working alongside First Nations people in exploring possibilities for nature-connected eco-tourism. Nature therapy will also offer an alternative path to health and wellbeing, recovery from painful loss and hope for those who struggle in daily life to find meaning in this stressful world.

As I write, our family is seeking to find a permanent place to set up home in the hills, nestled amongst protected state forest and freshwater springs. We long to grow our own food, foster regenerative land-care practices, learn to live more simply, and deepen our own spiritual connection with this place. We yearn to share our vision with others, in the short term offering a two-way, shared learning space for co-creating and workshopping, and in the longer term a healing sanctuary and affordable retreat accommodation in a bush location. I have no idea what this actually looks like; we trust that our vision for the regeneration of self and planet will grow organically, working with rather than against nature’s patterns and rhythms.

And so it is with a renewed sense of hope for humanity and the planet, that I embark on 2018. While that might seem like a lot of change in the wind, for my subscribers to the blog and podcast most things will stay the same. You will still be able to access my learnings on the journey in Indigenous social work practice as well as weekly podcast episodes of others’ experiences in social work with First Nation Australians. As we move forward, you may find I do more blogging about the integration of ecopsychology, ecotherapies and Indigenous ways of knowing and healing ourselves and the planet.

My hope for this space in 2018 is to ramp up the conversation, amplify the connections between us, and share the great work that is happening around Australia. If you’re engaging in Indigenous social work practice (or even just attempting to ‘walk the talk’), you have a story that others need to hear. Please join in. Send me an email and introduce yourself, comment on the Facebook Page, follow us on Instagram, volunteer to be a guest blogger or nominate someone for a podcast interview.

In the midst of the hustle and bustle of packing up and moving, my podcast recording equipment is now sitting in a storage warehouse in Brisbane. A small oversight on my part which I hope won’t affect broadcasting too much in the coming months. I have three episodes waiting in the wings and will bring these to you each Wednesday starting next week.

In signing off, I’d like to acknowledge the hurt and sadness that exists on this day around Australia amongst our Aboriginal brothers and sisters. While many see January 26 as a day to celebrate, the rest of us mourn. I support #changethedate to recognise this painful history and to choose a more suitable date to celebrate what it means to be Australian.

May you be calm and keep on walking.

Lucy

If you work in the area of trauma counselling, chances are you have an organisation or colleagues keeping a watchful eye out for the first signs and symptoms of burnout or vicarious trauma.

If you work in the area of trauma counselling, chances are you have an organisation or colleagues keeping a watchful eye out for the first signs and symptoms of burnout or vicarious trauma.