About five years ago, I was attending a conference in Alice Springs. Richard Frankland, an Aboriginal man, was presenting his research on Lateral Violence. After hearing this term for the first time a light bulb lit up. I now had a new lens to view the disturbing level of violence I was noticing in the communities I was working in. Not the fighting in the streets – the family feuding and the kids brawling – that is very visual. I’m also referring to the more sinister violence you don’t always see, but you feel and hear.

Later that year, I started getting emails about Lateral Violence from William Brian Butler. Butler was born in Darwin in the Northern Territory, following his Mother’s forced removal from his Grandmother where they lived at the detention centre known as The Bungalow in Alice Springs. Brian lived at the Bagot Reserve in Darwin with his Mother, up until the beginning of the II World War, which forced them to evacuate back to Alice Springs and be reunited with Family. Butler had been doing research using Facebook. His suspicions were confirmed. Not a lot of people had heard of Lateral Violence, let alone what to do about it.

So what exactly are we talking about? The legal definition says lateral violence “happens when people who are both victims of a situation of dominance, in fact turn on each other rather than confront the system that oppresses them both”. Paul Memmott defines it as “unresolved grief that is associated with multiple layers of trauma spanning many generations”.

I’d had a good understanding of Australia’s colonialising history and not surprised by the level of physical violence I was seeing. But lateral violence is even more subtle.

Internalised feelings such as anger and rage are manifested through behaviours such as gossip, jealousy, putdowns and blaming. It can include nonverbal innuendo like raising eyebrows and making faces, bullying, snide remarks, abrupt responses and lack of openness, shaming, undermining, social exclusion and turning away, withholding information, sabotage, infighting, scapegoating, backstabbing, not respecting privacy, broken confidences and organisational conflict.

During my time out bush, I saw lateral violence lead to more explicit conflict which broke up relationships, families and communities.

In response to the phenomenon that is Lateral Violence which is shared by colonised peoples across the world, Butler has taken upon himself to respond by leading the Lateral Love and Spirit of Care for all Mankind campaign. Butler urges his own people to put down their arms and stand their ground using unconditional love in the quest for healing and justice.

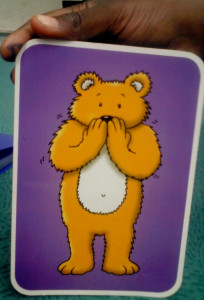

Barbara Wingard, an Aboriginal practitioner and teacher with the Dulwich Centre has drawn on the traditional of storytelling to educate Aboriginal people about the nature of Lateral Violence. Following the narrative concept of collective externalising conversations, one person interviews another who is role-playing the persona of Lateral Violence. Learn in such an engaging and interactive way makes it safe to explore what can otherwise be tricky territory. Here’s an exerpt….

What makes you powerful, Lateral Violence?

“I reckon I’m doing my best work when I get families to fight against one another … It’s fantastic when everybody wants to take sides. This creates a bigger divide. I can also stop Aboriginal people from working with white people. I do that pretty well and I confuse white people about Aboriginal culture too. I try to convince white people to think bad things about Aboriginal culture… In some Aboriginal communities I try to get people of Aboriginal heritage to be suspicious and judge each other by asking ‘who is Aboriginal and who is not really Aboriginal?… I start to manipulate who is and who is not (Wingard 2010).”

I have witnessed some great acts of Lateral Love now being taken by Aboriginal communities to counteract the devastation of Lateral violence. While working on the Tiwi Islands, a few years ago cyberbullying and sexting got out of control. The old people were becoming increasingly concerned about how young people were using mobile phones to send anonymous messages via social media that were mostly degrading, harassing or untrue. The result was conflict between young people, family infighting and even in some cases self harm and attempted suicide.

The community responded by organising several community meetings and the issue was taken very seriously. In what was a rather quick response, popular band B2M with the assistance of Skinnyfish came on board with a media campaign that would appeal to young people to raise awareness of the dangers of misuse of social media. Here is what they came up with:

Here we have a community recognising the problem, and rallying together to arm themselves with the skills and knowledge needed to take appropriate action. A Lateral Love Action!

For those of you who have never met Lateral Violence, I dare you to sit down and have a chat. You might be surprised to hear about the sneaky tricks of this insidious killer, friend of the coloniser who arrived by boat in 1788 and has been quietly working away in the shadows ever since.

References

Wingard, B. 2010, ‘A conversation with Lateral Violence’ in The International Journal of Narrative Therapy and Community Work, No. 1

Memmott, P. 2001, ‘Community Based Strategies for Combating Indigenous Violence’

Butler, B. 2012, ‘Zero Tolerance to lateral violence to improve the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Islander Peoples in Australia’