One of the things I have been most passionate about in my work with children and their families is being able to give children a voice. Sometimes this can be very challenging. Children can be left silenced by their experience, especially in situations of domestic and family violence. Feelings like shame, sadness, anger, guilt, despair and fear prevent children from being able to find words.

As a counsellor in remote communities, it would be very easy to become complacent and dismiss the effects of violence as normalised behaviours in children; because violence is something many children may witness and learn to live with. But it is certainly not normal and violence shouldn’t be tolerated. It is my experience on the Tiwi Islands working alongside local people that children, especially boys, are too scared to talk about the violence occurring in their families. It could cause further shame for them or expose them to further punishment or abuse if they speak out.

So the challenge is….how do you allow children to have a voice without exposing them to further shame or trauma? Of course, one does not necessarily have to speak about the details of a bad memory in order to begin the process of healing. In fact, neuroscience suggests that sometimes it is physically impossible to recall all the details of a traumatic event anyway, due to the brains response to toxic stress and its effect on memory. Some children may not be consciously aware of what has happened to them even though the body remembers.

The goal then is to help children integrate and transform their trauma experience without having to recall any facts. The child will be able to relate to feelings, thoughts, sensations in the body and compulsions to behave in particular ways, even if they do not link this to any past hurts.

One way I have tried to assist integration and help children to make sense of their experience is encouraging the use of ‘third person’ voice. Play using miniature animals or puppets, drawing or play-doh creates all sorts of opportunities for imagined creatures to tell a story. For me, the bear cards have been a great resource in shifting children into this safe space; to explore what might have happened for bear to have an angry, scared or sad face, what is happening in his body and what he is driven to do. The process also fits really well with the idea of ‘externalisation’ in narrative therapy, allowing the child to see that a problem sits outside of themselves, rather than taking up permanent residence inside them. I have written elsewhere about the use of masks in therapy to assist with externalisation of feelings which are impacting in negative ways on children.

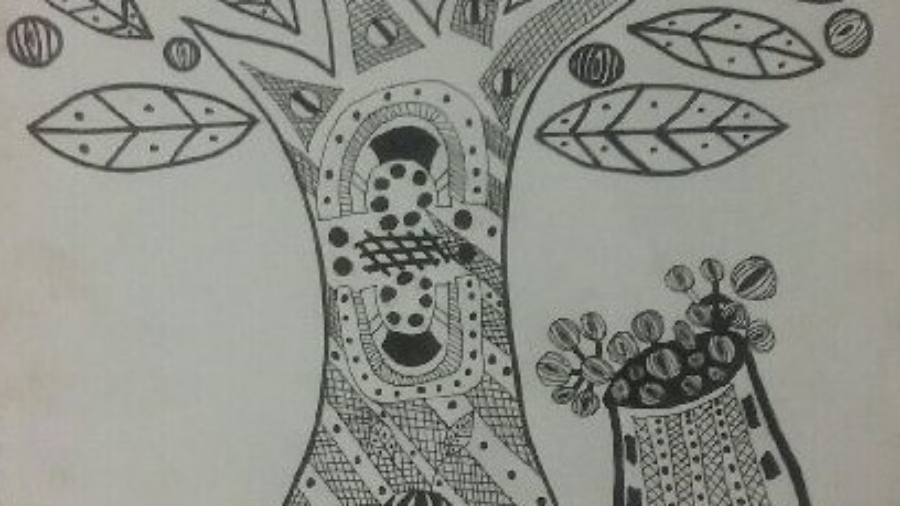

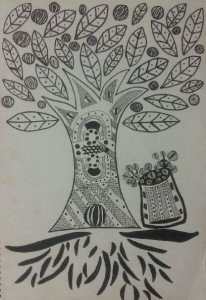

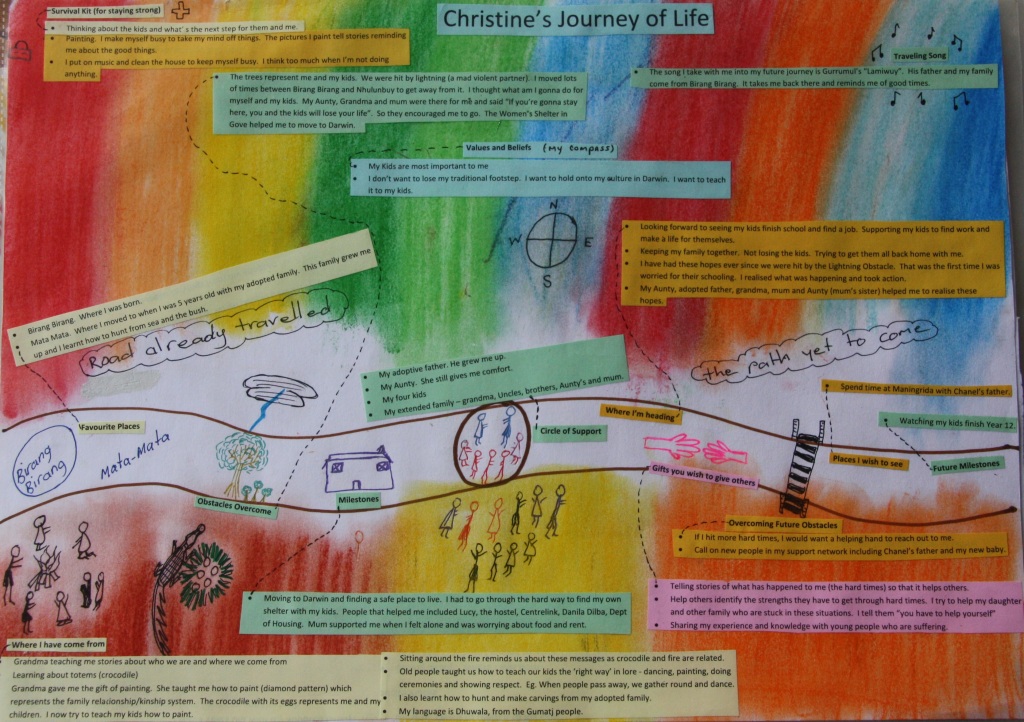

Another indirect way of assisting communication in therapy is through the use of metaphor. In my experience running group-work programs on Aboriginal family bush camps, I’ve discovered the power of using the tree metaphor to assist people to share their strengths, abilities and skills for getting through hard times.

It is through my discovery of the power of metaphor for communication and the challenge of working with Aboriginal boys, that inspired me to write a children’s therapeutic picture book. ‘The Life of Tree’ uses the tree metaphor to explore the issues of domestic and family violence. My hope was that by reading this story, Aboriginal boys in particular, might be invited into a safe conversation about their feelings, thoughts and actions in their own lives.

Over the past six months I have been mentoring Yolngu artist and friend, Christine Burrawanga, to create the images for the story. This is a story that is very close to Christine’s heart and so her strong culture, passion and enthusiasm to make a difference for her people has really shaped the book.

Our hope is that ‘The Life of Tree’ is a key to opening the door to the voices of children which have been locked away by the experience of violence. Healing from the trauma of violence can be a long journey. But if that door is opened ever so slightly as a child, perhaps the emotional burden they are carrying, will be lightened just a little bit.