An advocate for ‘two way’ relationships and “not being a seagull” – Toni Woods

Do you know what it’s like to meet up with an old friend you haven’t seen for years and feel like you picked up exactly where you left off? That’s what my conversation felt like this week on Episode 9 of ‘Talk the Walk’. Nine years after crossing paths on our respective journeys, I reconnected with an old friend and colleague, Toni Woods.

Toni now lives in Canberra and works as an Implementation Specialist with the Intensive Family Support Service (IFSS) which sees her travelling back to the Northern Territory to provide practice coaching with her team. Prior to that Toni worked in remote Aboriginal communities supporting women and children living with domestic and family violence, project co-ordination of child-friendly safe houses and community development with urban Aboriginal school communities around Darwin. Toni has worked alongside Aboriginal people in supervision and management, developing creative-culturally safe educational resources, training and mentoring, project management, counselling and family support. She is gearing up to head off to the SNAICC Conference in Canberra next week, to support her colleague Faye Parriman in presenting her amazing resource and share their current work with the IFSS project. Be sure to say hello, if you happen to be there!

I hope you enjoy my conversation with Toni as we look back on almost a decade of her incredible development work.

In this episode, we explore:

- Toni’s yearning to respond to social injustices and human rights violations she observed after arriving in Darwin and the NT Emergency Intervention was introduced

- What Midnight oil, nursing strikes and Jon Lennon has to do with Toni’s commitment to these ethics and values

- How challenging moments are actually opportunities for good work to happen (especially when you have the courage to talk to the Federal Opposition Leader!)

- Hearing stories from people, ownership of story and the dilemmas around sharing story when there are issues of collective injustice

- The joy of work that advocates for and engages local community members in making decisions about their own families and communities

- The skills and knowledge needed to co-ordinate an urban Aboriginal community project to improve school attendance; and the learnings and outcomes achieved

- Lessons learnt about the importance of the implementation phase in running a successful project

- The role of the Parenting Research Centre and the development of culturally safe resources available through the Raising Children network

- Toni’s long established collaborative relationship with Senior Aboriginal woman Faye Parriman and the cross-cultural work they have achieved together

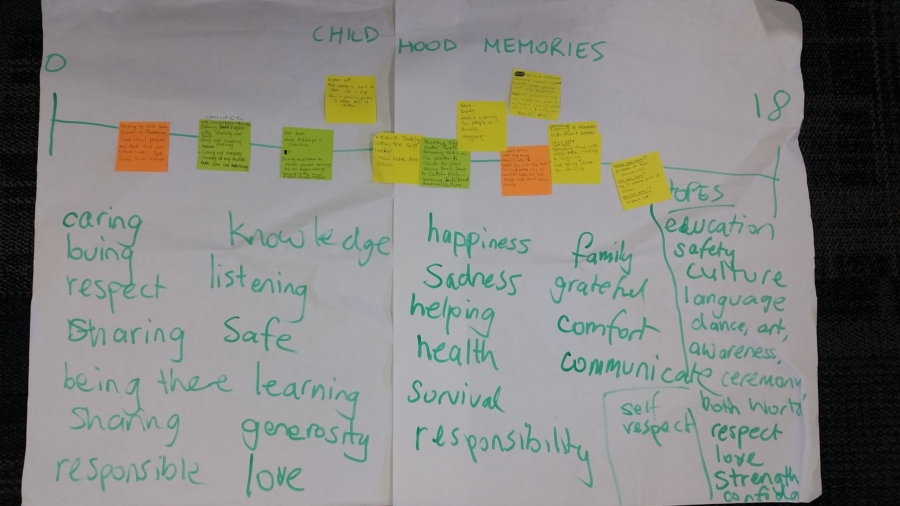

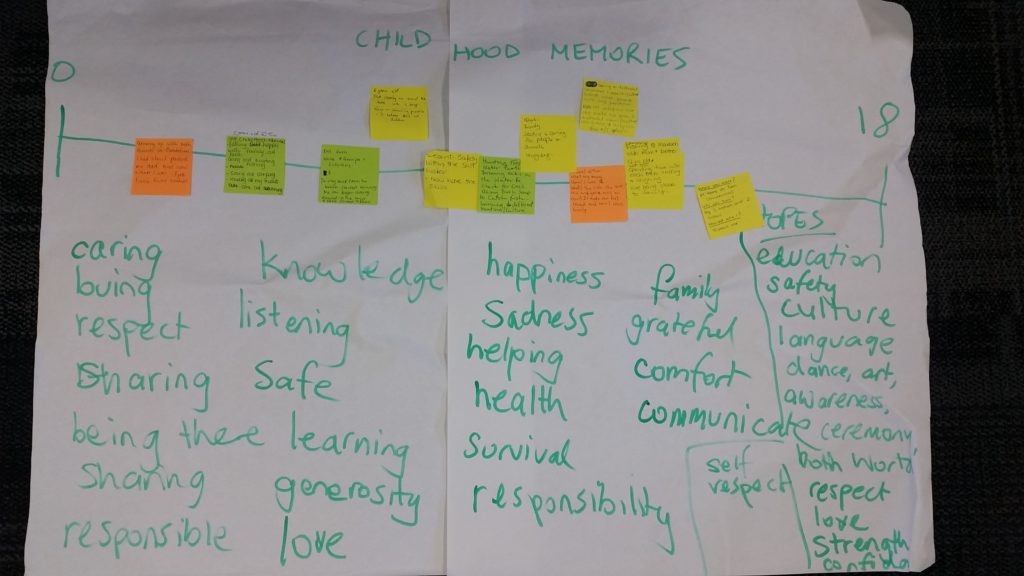

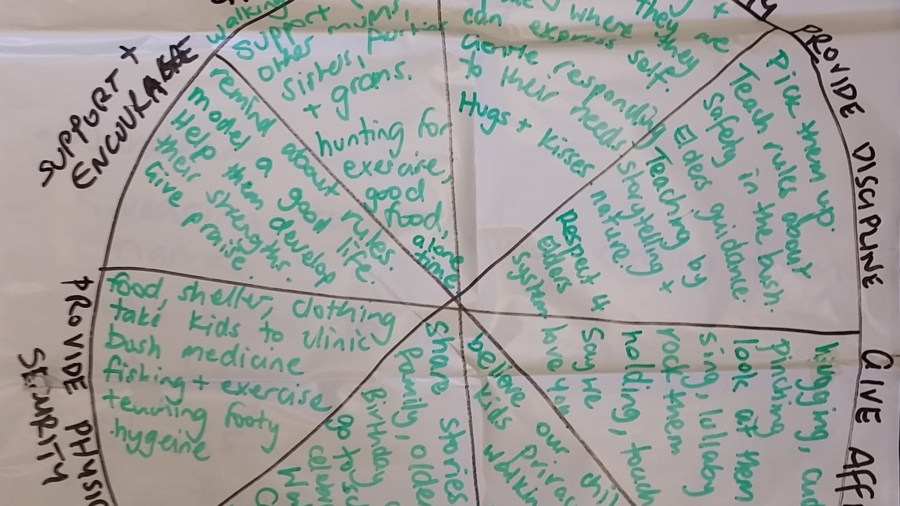

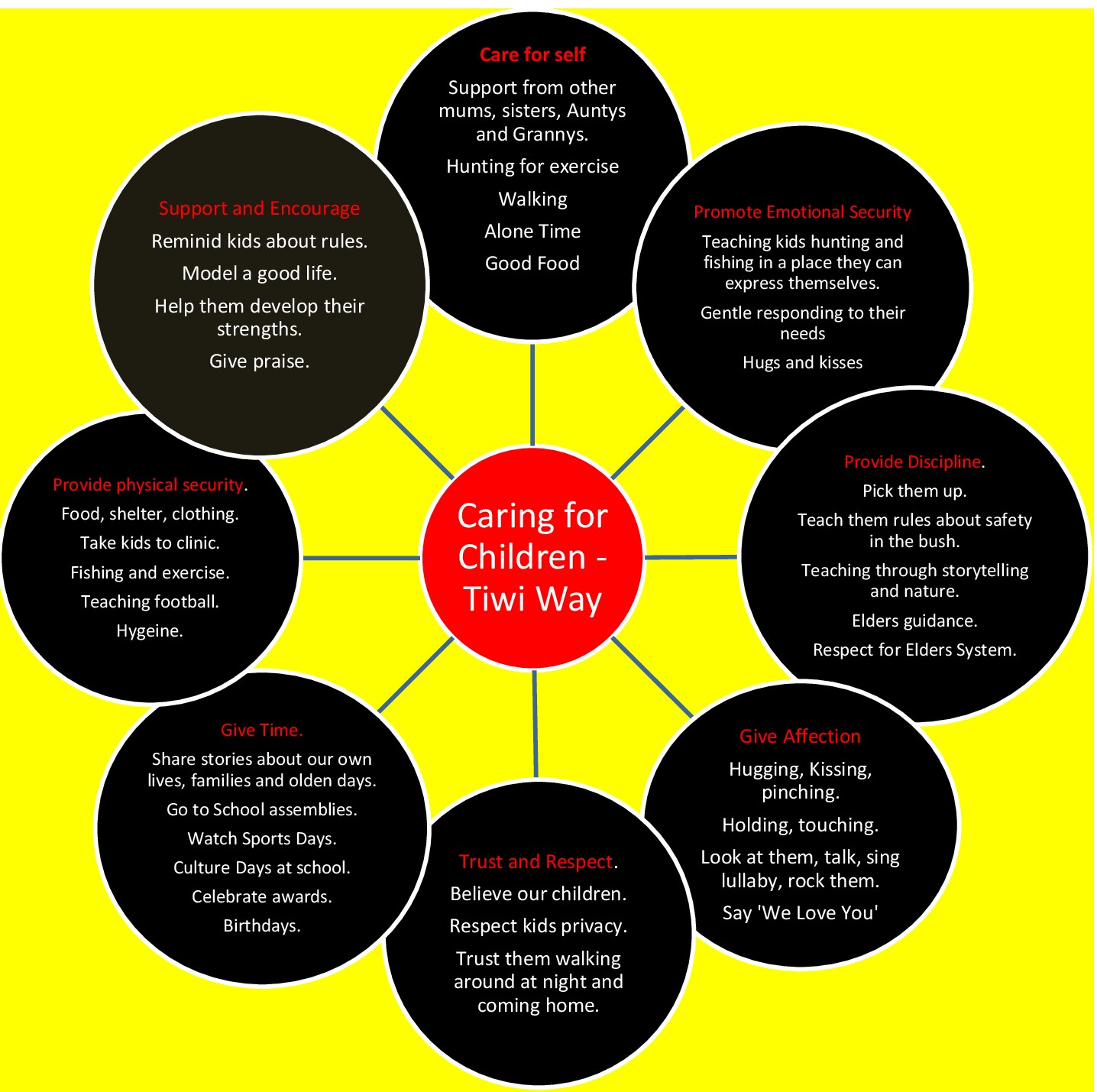

- How the Yarning Mat tool came about through Faye’s visionary dream, a tool to engage Aboriginal parents in the Intensive Family Support Service; an introduction to the elements and how it is used from engagement and assessment to review and closure.

- Reflections on Toni’s ‘two-way working’ relationship with Faye and the elements that built respect and trust

To listen to this episode simply click on the Play button below or listen via the Stitcher App for iOS, Android, Nook and iPad.

You can also subscribe to podcast and blog updates via email from the Menu on the Home Page.

Don’t forget, if you or someone you know would make a great interview on ‘Talk the Walk’, send us an email from the Contact Page.

Things to follow up after the episode

Faye Parriman on the Yarning Mat

National Implementation Research Network

Contact Toni Woods on LinkedIn or via email at twoods(at)parentingrc.org.au

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS