On location at healing bush camps on Bathurst Island

Yippee, you made it. Welcome to my first ever episode of ‘Talk the Walk’ – the podcast putting legs on social work in Indigenous communities through story.

This podcast will appeal to social workers that find themselves in many different contexts in Australia, who come across Aboriginal or Torres Straight Islander people in their work, as well as new graduates contemplating this area of practice. The podcast may also appeal to social workers internationally, interested in learning more about what its like to walk alongside Australia’s First Nations peoples.

And now to my first guest.

Working out bush comes with rewarding challenges

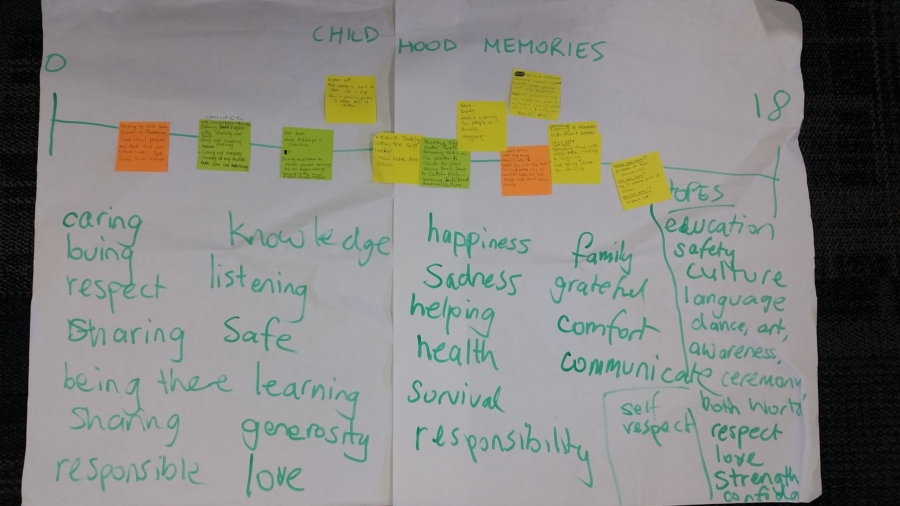

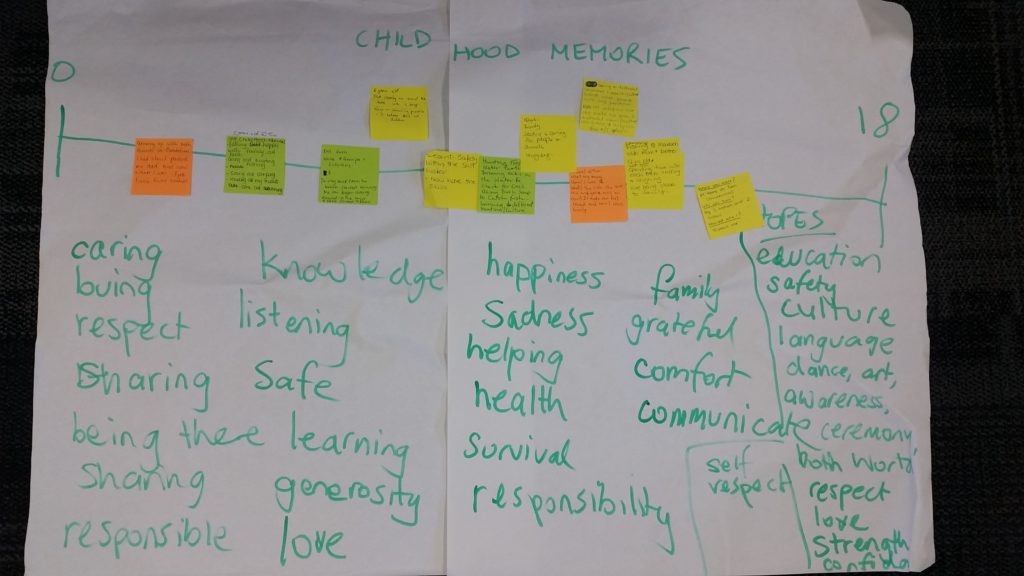

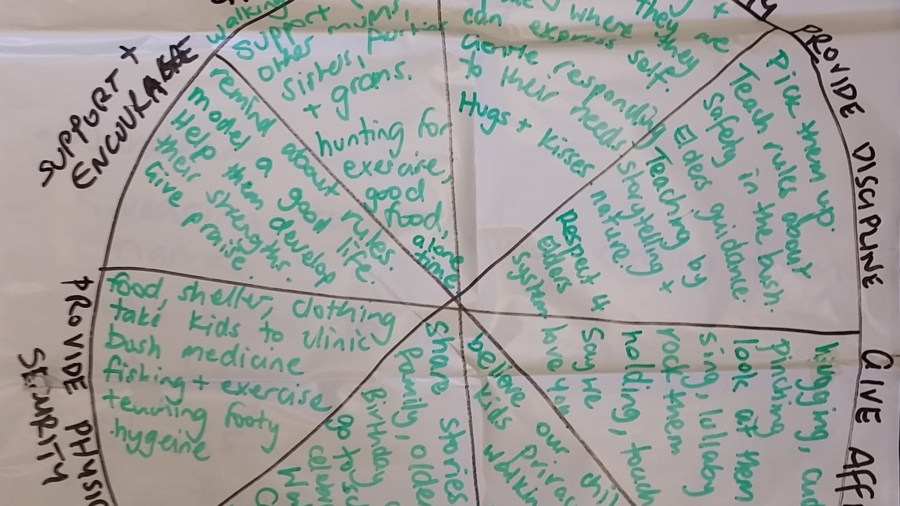

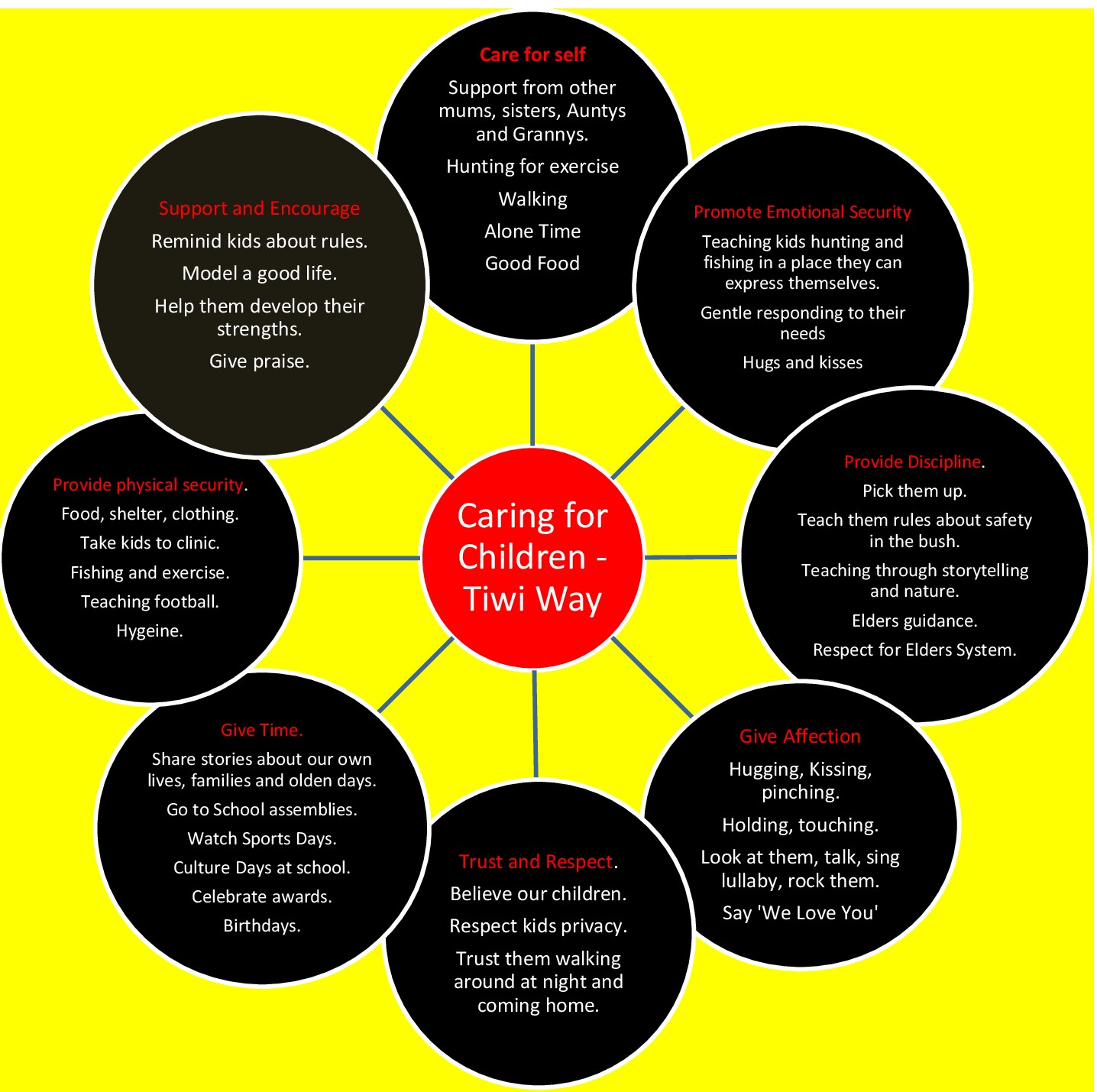

Rather than sink, Lissy Suthers chose to swim when she moved from Ipswich in Queensland to the Northern Territory in 2012. Fresh out of university, her first placement was co-ordinating and facilitating healing bush camps for families on the Tiwi Islands. Having supervised Lissy during this time, it was my absolute privilege to interview her for my first episode of ‘Talk the Walk’.

Although she might look like she’s drowning at times, Lissy has moved her way up through Relationships Australia NT to the role of Manager of the Children’s Therapeutic Team, operating on the Tiwi Islands, Darwin and Katherine.

This is a beautiful and honest conversation with a social worker who survives on humour and laughter. There is no sugar coating in this episode. Enjoy!

This episode explores:

- Why I decided to start this podcast

- Why social workers move up through the profession in remote areas of Australia very quickly

- The importance of Aboriginal history and world view in social work study

- The values, life experience and family influences which have shaped Lissy’s social work journey

- White privilege and class privilege and it’s impact on social work practice

- Reflections on student placement in a remote community

- Differences in communication

- The unique skills and knowledge Lissy has developed from her experience in remote work

- Considerations for entering a community for the first time

- The values and ethics which shape Lissy’s culturally fit practice framework

- Equality and the myth of ‘all the free stuff that Aboriginal people get’

- The difference between social work in Indigenous communities and social work in other contexts

- The development of inner and external resources

- Encouragement for new graduates to dive into social work in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities

We hope you enjoy this episode. If you or someone you know would make a great interview on ‘Talk the Walk’ send us an email from the Contact Page. I am currently working on listing ‘Talk The Walk’ with podcasters including iTunes to make subscribing easy. Stay tuned.

Things to check out after today’s episode

Lissy’s reflection on student placement on the blog – ‘Culturally Fit Social Workers: We need more of you!’

Connect with Lissy on LinkedIn

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS