I was first introduced to Narrative Therapy in 2006 after graduating with my social work degree in Brisbane. But it wasn’t until a few years later in Darwin that the penny dropped on how this approach might actually sit comfortably alongside the worldviews and cultural perspectives of Aboriginal people whom I was working with. A one week intensive at the Dulwich Centre in Adelaide introducing me to Collective and Community practices from a narrative approach was the start of a journey of sharing these ideas with my Aboriginal colleagues and ‘having a go’ to see what works.

The following reflections show how my practice approach has been influenced by narrative therapy ideas.

Double Listening

The problems that affect the lives of Aboriginal people can often be presented in a way that is disabling or weighing them down heavily; for example, domestic violence that has gone on for many years or issues associated with poverty that affect people’s stress levels. This negative story can come to dominate people’s lives so that it is the only one they come to believe about themselves and other people tell about them.

However, people have many story lines running through their lives. Perhaps they have simply lost touch with the things that are important to them and they give meaning to? In a process of ‘double listening’, we are continually looking for doors into the alternative story, as the problem-dominant story is one that Aboriginal people can fall back into again and again.

Externalising

The person labelled as ‘angry’ or ‘naughty’ by others can sometimes internalise this view about themselves. The process of externalising helps us to “separate the problem from the person”. A lot of my counselling work has involved externalising the feelings of children who have been labelled by their communities or families as angry, naughty, bad, lost, lonely, no-hoper, mad and stupid. Through exploring the “strong story” using things like drawing, painting, clay, puppets and story writing children come to see that ‘the problem’ they are experiencing does not reside inside themselves, but is external to them, possibly as a result of someone else’s problem behaviour in the family. Children have such amazing imaginations when it comes to naming the problem and can articulate the ‘monster’, ‘devil’ or ‘alien’ as no longer having hold over their lives.

Resistance

Aboriginal people who have experienced trauma are often overwhelmed by feelings of shame, thinking somehow they are to blame for their problems or perhaps they invited it. However, no‐one is a passive recipient to trauma. Even in the most difficult of circumstances when it was not possible to avoid the trauma, people still take positive steps to stand up against it, resist it or protect themselves from its effects (Yuen 2009). However small these steps might be, they indicate people are responding because it challenges their values and who they are. What is it they hold precious in their life that they would respond in this way? What is it they strongly believe in, that has been threatened? By exploring and thickening the strengths, skills, values and abilities that help them through difficult times, Aboriginal people reclaim strong stories of hope and resilience and move towards healing. The narrative approach gives Aboriginal people a safer place to stand to explore their experience without having to re-tell any traumatic details.

Collective Narrative Documentation

Narrative practice is interested in linking the individual experience to the collective; our individual problems are instead viewed as social issues. When listening to Aboriginal people’s experience of trauma, we are not only listening for individual accounts of how people responded to hard times and developing a rich narrative together, but looking for opportunities to link their life to some sort of collective experience. In this way, people speak through us, not just to us (Denborough 2008). Some of the children I worked with wanted to share their stories of living with violence or bullying with children from other communities. I became the deliverer of special messages between children who willingly offered up their stories if it meant it would help someone else. They often reflected “I am not alone in this” or “My experience is helping someone else”.

When people have an opportunity to anonymously share their stories with a broader audience, like another community, they gain a sense of contribution to the lives of another who may also be experiencing hard times. In my work with Tiwi at Family Healing Bush Camps, community members were invited to share what skills, knowledge and abilities they used to get through difficult issues such as family and domestic violence, substance misuse in the family and having their children taken by welfare. A written collective document was given back to the participants to share with other communities. Such documents can be powerful methods of generating a social movement towards change, healing whole communities of people who share stories with each other.

Tree Of Life

Collective methodologies such as the Tree of Life and Team of Life have shown to be extremely effective at allowing children and young people who have experienced trauma or significant loss to speak about their skills and knowledge in the comfort and security of peers. These metaphors offer Aboriginal people safe ways of exploring the difficult events of life like “the storm which hit our family” or “having to defend oneself from attack”. Family members and Elders who act as outsider witnesses to children’s experience are valuable players in validating these stories. The artwork generated from this group-work can also be shared as a collective document of children’s resilience, knowledge, hopes and dreams with other groups around the world.

Collective Narrative Timelines

Collective Narrative Timelines are also a well documented narrative practice for using with groups. I used this methodology during groupwork with Aboriginal women to help them reflect on their own childhood experiences and how these memories have impacted on their own parenting. Collective narrative timelines are great for the beginning of groups to help participants develop a connection very quickly around a shared theme, while also acknowledging the diversity of experience in the room. You can read about my process of using Collective Narrative Timelines in a previous blog.

For more resources and ideas on narrative practice with Indigenous communities, explore our Direct Practice and Professional Development Libraries.

References:

Denborough 2008, Collective Narrative Therapy: Responding to individuals, groups and communities who have experienced trauma.

Yuen, A. 2009, Less pain, more gain: Explorations of responses versus effects when working with the consequences of trauma.

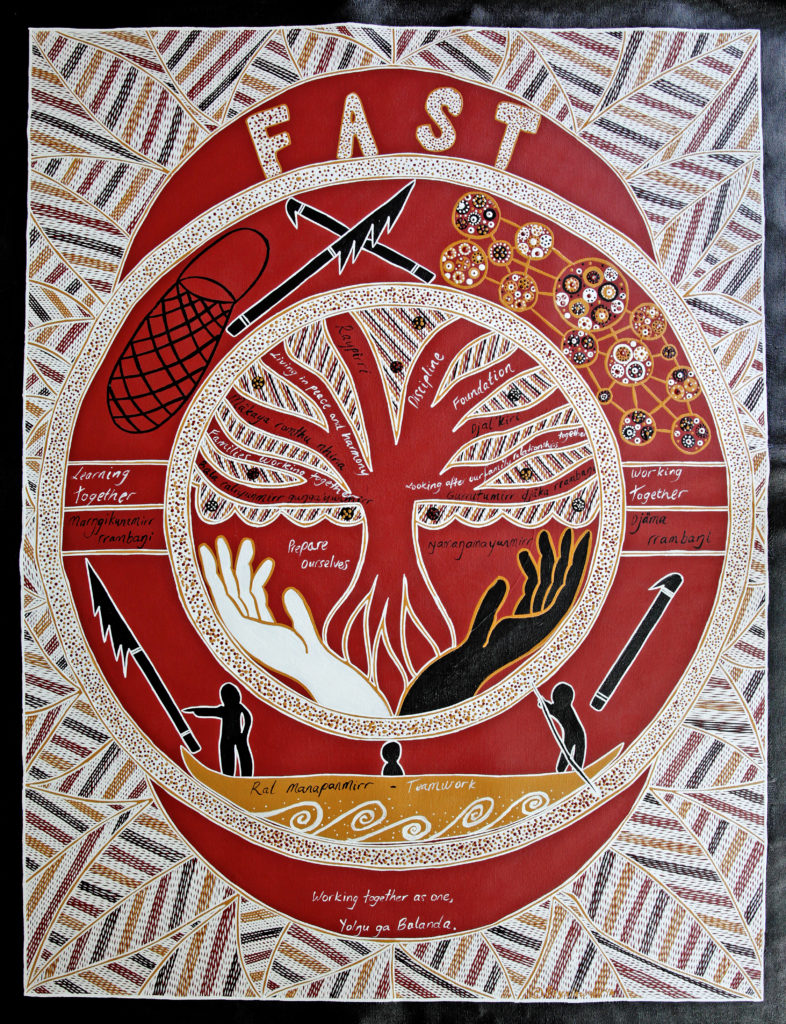

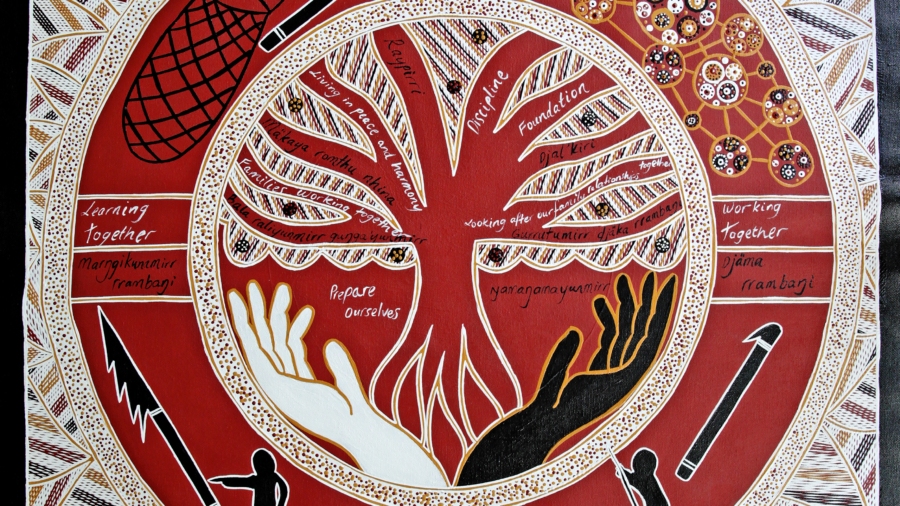

In this episode of Talk the Walk, we delve into the working life of Malcolm Galbraith, Manager of Families and Schools Together (FAST) in the Northern Territory. We discover not only what makes FAST one of the most successful strengths-based programs in remote Australia, but what drives the man behind the project. A man of strong Christian faith, Malcolm admits some of his ideas might be controversial, yet the evidence speaks for itself – Yolngu people love it! Before you scoff at the idea of bringing an American-based program into an Indigenous Australian context, listen to this story. As intriguing as it is thoughtful, this behind the scenes tour of FAST NT may just turn your worldview on its head.

In this episode of Talk the Walk, we delve into the working life of Malcolm Galbraith, Manager of Families and Schools Together (FAST) in the Northern Territory. We discover not only what makes FAST one of the most successful strengths-based programs in remote Australia, but what drives the man behind the project. A man of strong Christian faith, Malcolm admits some of his ideas might be controversial, yet the evidence speaks for itself – Yolngu people love it! Before you scoff at the idea of bringing an American-based program into an Indigenous Australian context, listen to this story. As intriguing as it is thoughtful, this behind the scenes tour of FAST NT may just turn your worldview on its head.