I’ve been struggling with this thing I can only describe as ‘Numbness’.

Numbness can set in randomly for no reason at all. Or if something happens that I feel sad about. It can happen at home or at school. It seems to like invading my weekends.

It’s like the light bulb goes out in me. And I lose the thrill of doing anything.

Numbness can make me not feel anything. I just feel tired and want to be alone in my room. I’m even too tired to fight with my siblings.

Numbness takes away my motivation and makes me not want to do any of the stuff I really like. It takes me away from being with my family.

When numbness is around, I stop taking care of myself. I stop showering. Numbness is not something I can just wash off.

Numbness throws me out of routine. There’s no in between. I either eat too little or eat too much, sleep too much or not enough.

It makes me lose all hope when it tries to tell me “Oh well, it is what it is”. If I fail an assignment, no big deal.

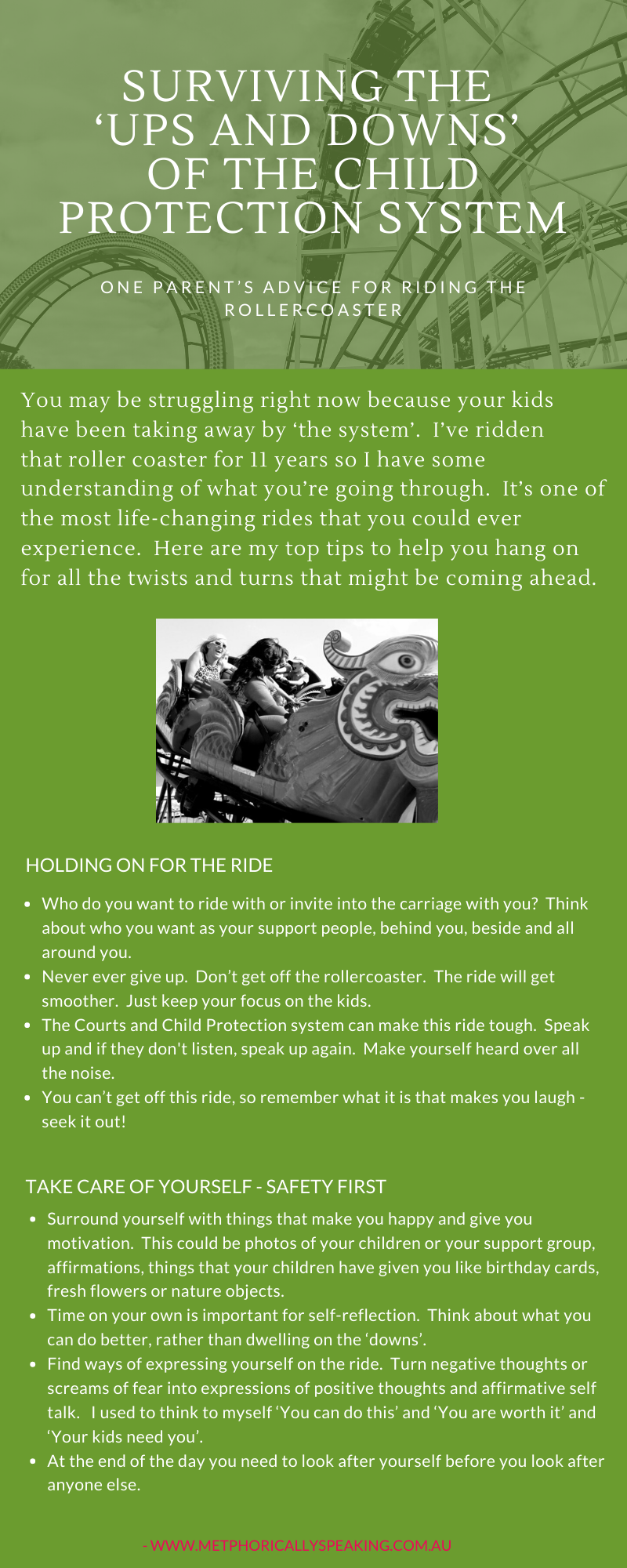

There are things I try desperately to hold onto when I notice Numbness trying to take me away from the things I care about. One of these things is LOGIC. I can call on logical thinking to try to challenge the tricks and tactics of Numbness.

I like bingeing on my favourite TV shows. This makes the light bulb really bright in me. I feel happy and it influences me to do more of my favourite stuff.

Numbness has not been able to steal way my personality when it comes to kindness. Even when I’m not at my best, I am still kind and friendly to others. I still give a bright smile to people I care about. I tell my friends to stay strong even when I am feeling worthless. I know I’m a good person. Even at my weakest, I still give advice to my friends, even if it’s a bit quicker than usual. I will never say “I can’t help you”. I believe it’s important to be friendly. I hate the idea of making people sad for no reason. If I snap at them, that hurts me. I won’t let Numbness take away my goodness.

If my favourite anime character Erza was fighting Numbness, she would never give up. She is always thinking of her friends, she keeps fighting for them. She reminds herself of what she is trying to protect. She cares a lot about other people and gets strength from helping others. There are moments when I feel accomplishment when I help other people.

I won’t go overboard trying to chew someone up. That takes too much energy. In the past one friend dragged the energy out of me. When they are upset, I don’t put much energy in. I don’t want to get drawn into their stuff. I have to try to put boundaries in for myself.

Erza wouldn’t let people walk all over her. She would say “I’m not an inanimate object”. She has good friends that don’t try to use her. I want to be able to stand up for myself more. If no-one is going to stand up for me, I need to do it for myself. If there are people picking on me, I just ignore them and walk away.

Opportunity to be an Outsider Witness to this story

After reading this story, we invite you to write a message to send back to the author. Here are some questions to guide your response.

- As you read this story, were there any words or phrases that caught your attention? Which ones?

- When you read these words, what pictures came to your mind about the authors hopes for their life and what is important to them (ie. dreams, values and beliefs)? Can you describe that picture?

- Is there something about your own life that helps you connect with this part of the story? Can you share a story from your own experience that shows why this part of the story meant something to you?

- So what does it mean for you now, having read this story? How have you been moved? Where has this experience taken you to?

Please contact us with your response and we will forward your message to the author of this story.